I remember listening to Focus as a teenager and feeling the convulsive, architectonic shift of possibilities blistering the material of my otherwise under-seasoned reality. Cynic’s debut fundamentally altered my understanding of what I could demand of art—whether it was created by others or by myself. In fact, it’s a personal axiom that Focus, (along with Faith No More’s Angel Dust,) permanently altered not only the way that musicians in the extreme music sphere composed and performed but crucially, how its audience actually listens to music. Just try to envision where the scene would be without those two records and the new panoramas that they introduced to us. They shoehorned the hereafter into the here and now; the improbable elided with the probable.

I also remember the expectations with which I saddled Cynic’s sophomore ‘comeback’ album Traced in Air. It was infeasible that it could provide me with what I—in my heart’s core—insisted that it must, (that is, to give me the exact feeling of listening to Focus while simultaneously presenting that feeling as entirely original and startling.) Nevertheless, that was my demand and I was therefore predictably frustrated. I wanted Cynic to act as a vehicle on rails and expected the dopamine to flow even as the thrills of the ride itself remained static. I don’t know about you but Traced in Air took a great deal of time for me to cozy up to. Cynic was not -nor has ever been- on rails and every one of its records has required taking the time to actually acquaint oneself with on an individual basis. (What a concept, right?) Cynic makes ‘Cynic Music,’ a thing unto itself which happens to be exacting and fluid and emotional and fundamentally alien.

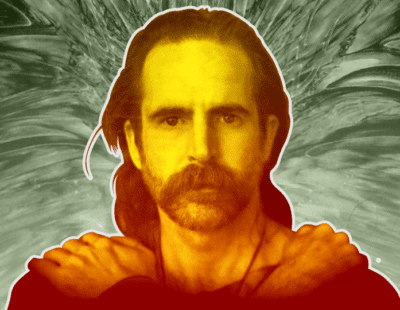

After spending so much time mulling over the band and their debut record with Liam Wilson for the majority of this series, it felt not only appropriate but borderline obligatory to cap the entire shebang via a chat with Paul Masvidal. Of course, the nuts and bolts of Focus as a work of music have been extensively explored; my aim was to be educated on the genesis of Cynic’s conspicuous spirituality. Paul was more than happy to enlighten me, (and the pinhole leaks in my own spiritual comprehension have never been more conspicuous.) Suffice it to say, if you’ve studied and admired Cynic’s debut over the years as Liam Wilson or myself have, consider this closing Fallow Heart transmission a course requirement.

I got in touch with Paul just as he was just setting off to Miami to oversee the remix and remaster of Focus for its 30th anniversary. Perfect. Cynic has reached the ideal altitude for both stargazing and profound circumspection. We’ll be sailing deep into the hinterlands of memory but let’s begin with a bit of more contemporary lore first, shall we? Oh, and FYI: we’ll be piloting through some violent turbulence, there are no exit rows, there is no tarmac, your luggage has been lost on principle and the present moment is your one and only flotation device, (but, hey, at least you get to keep your devices on). Tray tables up.

We are always in transition.

If you can just relax with that, you’ll have no problem. —Chögyam Trungpa

Fallow Heart: So much seems to have been shaken loose in your world directly on the heels of Kindly Bent to Free Us. When you were going into record Ascension Codes and Sean Reinert had only just passed away and then Sean Malone vanishes and you have all of this loss weighing on you, does the album that you’re gearing up to record still feel like a genuine expression or did you feel estranged from it?

Paul Masvidal: Man… I had to push through all this paralyzing trauma and discomfort. I can’t tell you how many conversations I had with Michael [Berberian] from Season of Mist saying ‘I can’t do this. I can’t finish this record; it’s not going to happen.’ Like, bawling, crying… I was a mess. I had lost my band; there was no band! I mean, I forged my identity with those guys. It’s beyond family because you make intense art together, you live together… It’s such an entrenched relationship with so many layers. And Reinert and I having our falling out …it was just a really complex relationship that we had, incredibly creative and in some ways deeply telepathic. We had that incredibly unique tension that could produce interesting music. Another layer is just the unresolved nature of his loss because first I grieved losing him as a band member, (for the longest time I carried this hope that at some point we’d reconcile,) and then to physically lose him… it was for me one of the most significant moments of my adult life. Everything is suddenly turned on its head. I suddenly don’t know who I am or what the hell’s going on. It’s been a huge unraveling that feels incredibly surreal.

Regardless, I had to finish the record so I pushed through all of this discomfort and—to bring this to a spiritual practice—I think years of doing ‘duration sitting’ where you’re just sitting for hours and solely working with your mind goes hand in hand with a situation like this where you have to push through a hell of a lot of discomfort and meet all of these states of mind and keep going and just dealing with all of it. They talk about the five hindrances in Buddhism and for me it was all there. It was next level and it seeped into the music. I feel like what got imbued into the record was this pranic, Shakti, performance energy that was just on fire. At the same time, Ascension Codes also has this ethereal quality. I heard it recently with a friend who cranked it up in his car and I thought, ‘Wow, this record’s actually kind of soothing!’ It’s not as aggressive or heavy as I remembered. But it’s hard to be objective with all this stuff, even now. It’s almost an out of body experience.

FH: It is hard to be objective, I agree… You know, I used to put a lot of stock into objectivity when I first got into music journalism, (there was a lot of ego involved in it for me.) I felt like music critics were this rarified class of people who could listen to something totally objectively and say, ‘this is quality and this is not. This deserves your time and this doesn’t.’ I hungered for those credentials. But as time went on I became increasingly uncomfortable with that. After I discovered meditation and Buddhism and jettisoned a lot of old rage that I had, it happened to roughly coincide with Albert Mudrian suggesting that I helm this column. My initial idea was to write about Buddhism and my experiences with Eastern philosophies to other metalheads but over time what I’ve found is that, essentially any new discipline that you adopt (whether it’s a spiritual practice or martial arts or becoming a vegan or whatever) for the first leg of your journey, all you want to do is fucking talk about it to everyone; just get in their face and tell them about what you’ve discovered and how great you feel and how they should definitely be doing it too. But after a while, that new discipline becomes so much a part of who you are that you become too busy living it to be talking about it all the time.

Masvidal: Exactly! And that first part’s especially interesting because these are conversations that Cynic used to have all the time. In the age of the internet it’s like someone starts a blog and all of a sudden they’re a ‘so called’ journalist. We were so annoyed by that that we became very anti-press. I’d say, ‘I’m not going to do interviews with ‘Joe’s Blog’ out of Ohio because he doesn’t know what he’s talking about!’ Real journalists are people who’ve done their homework and understand art and have real insight. We used to rely on those people to get input into how to decipher and interpret things and I feel like it’s gotten watered down in this sea of over-saturation. So I get what you’re saying but I still have a lot of respect and regard for actual journalists. It’s important. In some ways it may be as important as the art itself. It’s a way of seeing.

FH: Right! The peculiar aspect is that in our heart of hearts we want to share what we’re experiencing so through that lens, criticism makes absolute sense. You want to share how this or that work made you feel. It doesn’t have to have anything to do with the actual merit of the art itself, it’s a mechanism for digesting our experiences. But when you’re talking about a record that can sound so different depending on if you have the day off of work or if you just had a huge blowup with your significant other, it’s like ‘how can you sit at your computer and write so glibly about what someone else created when at least a large portion of what we’re talking about is really a reflection of you, your temperament and your preferences?’ At the same time, I’m fascinated by reviews and absorbing other writer’s impressions…

Masvidal: Well, this is the Cynic story. I mean everyone destroyed us and then 20 years later they’re like, ‘I love Focus!’ It’s like, ‘No! You didn’t love Focus. Sure, now you’re saying that it’s cool but you weren’t there for us.’ And in some ways all of that criticism killed us, you know? We felt so discouraged by the scene and we felt so out of place it was like, ‘whoa; we don’t belong here!’

FH: Okay, so now you’re driving towards what I wanted to discuss with you. As Liam Wilson and I were talking about Focus and the impact that that album has had on his life we were obviously discussing you and we had questions about what your life was like prior to Cynic and especially how you came to have the belief structure that you do. What drew you to Yoga and Eastern philosophy in your youth and what did it offer you that you weren’t finding outside of those systems?

Masvidal: Well, I think part of it came down to being raised in a non-religious home. My mother was into New Age stuff and she was taking me to psychics and astrologers and I remember one astrologer in particular giving me the Yogananda book [Autobiography of a Yogi]. I was also going to an occult bookstore down the street in my mom’s neighborhood. I’d ride my bike to this place and pour over stuff; I just naturally had this inclination. I remember my mother taking me to bookstores because I was just such an avid reader and she’d say ‘get whatever you want’ and I remember buying a book on Magick as well as a copy of The Satanic Bible, (I was trying to be rebellious, you know?) But my mom was so cool that I had a hard time shocking her. I had that kind of upbringing where it was all open; there wasn’t anything to rebel against… I always had a lot of empathy for friends who did grow up in restrictive religious environments. They had to go to church and parents were telling them, ‘this is what you’re supposed to believe!’

Anyway, my brother’s [Maheshananda] also a Yogi. He makes a living that way and puts out books… I’ve always thought that it’s not an accident that the two of us ended up deeply engaged in these kinds of interests, you know? But I think it all started with having a home environment that was just open and accepting. My mom was curious about things and she basically invited me to be curious about everything too. I remember, she was reading a Shirley Mclane book called Out on a Limb. It was a real breakthrough piece of media just in terms of introducing spiritual concepts to pop culture. In the movie she talks about a bookstore called The Bodhi Tree which was a famous bookstore in West Hollywood from back in the day. So I had this fascination with The Bodhi Tree and I would contact them when I was a kid, (I remember them faxing me instructions on how to read the I Ching.) So when I finally got to visit that store my mind was blown because it was like a spiritual library, you know? This maze of halls and little crevices and nooks where there were just all these books based on different themes related to spiritual topics and they had this tea that you could serve yourself; I mean, the place was incredible; it just had a vibe. I moved to L.A. in my mid-20’s so of course I frequented it all the time and I’ll never forget… Well, let me back up: I got into the Paramhansa Yogananda stuff as a teenager and by the time I was 18 years old I was a Kriyaban [an adept in the Yogananda order], (the Focus album was all about that.) I was densely immersed in Yogananda and all of the stuff that I was learning and absorbing from meditation practices and visualizations. You know, I even got permission from the organization to use a prayer of his for the song “Sentiment.” It was my entire world! But I’ll never forget being at The Bodhi Tree years later in my mid to late twenties with a Yogi friend, (who’s now a really happening and amazing teacher,) and him pulling out a Chögyam Trungpa book and saying, ‘Now, this is the dude!’ And I was immediately pulled to it. That book ultimately led me out of a lot of my old [Hindu] practices and on to the whole Shambhala and Tibetan Buddhism scene. That really became a kind of doorway for me; the path kind of opens itself up, you know what I mean? Certain teachings just resonate with you and the reason that I went more along that path is that I found that it contained a lot of things that were especially interesting to me: Shamanism, Magick… it got into all of these deep practices and although the more secular/religious aspects of Tibetan Buddhism turned me off, the actual sitting practices and the practical aspect of working with your mind…man! That stuff just got me, you know?! To this day I still consider [Chögyam] Trungpa my primary teacher. He was so clear and cognizant; he could just tell you everything. His most recent [postmortem] book that came out is called Cynicism and Magic. I would always defend a Cynic as being a Yogi. Obviously the word has changed and it’s been skewed in modern contexts so people have this negative association with a cynical person. I mean, it’s okay, words do change with culture and with time.’ But it’s interesting how Trungpa reclaims it in this book and talks about the use of cynicism as a means of discernment in the spiritual path. It was so beautiful to me that this great teacher bridged the gap and finally explained the roots of this word in the context of Buddhism.

FH: Going back a little, as an 18-year-old, things are really beginning to gel for you and you’re beginning to grasp certain concepts that will prove to mean so much to you for the rest of your life. Did your sexuality make sense to you at that point? What role did it play in this aspect of your journey?

Masvidal: You know, it’s interesting. A point that I feel like I should bring up is that I was committed to being an exceptional musician. I was committed to really developing my craft and my skills as a songwriter and a guitarist so I practiced like a maniac, you know? I still have that drive but what I’m saying is that at that age it went hand in hand with meditation and a spiritual practice because, (especially in considering the original Cynics,) it requires all this discipline, right? So I was really committed to fasting and… you’re just not giving yourself all of the pleasures of life, you’re doing the hard work. And so it was more of an internal process and it went hand in hand—the spiritual practices and the role of a driven, really committed musician—all the internal work and the insights gained from the sitting practice and how that correlated to playing guitar and crafting songs and the meaning that went into the songs. So, to answer your question, no. What’s interesting is that although I was ‘out’ to myself pretty young, (by my late teens I’d started to come out to my family and my friends) overall, I just laid low. I think it was in my early twenties that I began to really be more out with it but still I felt like I really had to be careful because, (especially in the death metal scene) it felt really unsafe. I was around people who were saying ‘faggot’ and it was a really homophobic and misogynistic scene, you know? We didn’t fit in. We wore cheap silk shirts and baggy clothes and Ganesha T-shirts and tie dyes while playing this weird, prog/death metal stuff. We definitely didn’t have the look. It was difficult because the tolerance just wasn’t there at that time. Also, when I was ready to completely ‘come out’ and actually explore my sexuality, AIDS was ravaging the world, (and in particular this country.) Where I lived in Miami, a lot of gay men were going there to die. It was like a whole population of them descending upon South Beach just to pass away, (I guess it had something to do with the warm weather…) So it was really a thing where I started to see that there was this fucking plague that’s wiping out gay men and it pushed me back into the closet and I basically went celibate. I was terrified of hooking up because I thought that I could be next. And who knows? That reaction could’ve saved my life, you know? It was everywhere at that time and a lot of people were dying and so I just went further and deeper into my music. It’s amazing when you repress certain things how it can be expressed creatively. I mean, that’s happened throughout history. People repress their sexuality or certain qualities about themselves and then they wind up making this beautiful art, you know? And I think Cynic had that kind of pressure where we really wanted to be free and gay. Sean and I had that together and yet we couldn’t so we said, ‘fuck that then. We’re going to be crazy, killer musicians.’ That kind of got channeled into being more intense players and it became our weapon. It became our identity.

FH: That’s so fascinating! And it makes absolute sense. It has a certain elegance to it but it’s incredibly painful at the same time. As your career was beginning to pick up steam—first with Death and then with Focus—was there a point at which you became concerned that you were having to compromise some aspect of one discipline for the other? What I’m asking is, was metal and touring difficult for you to reconcile with your spirituality?

Masvidal: Oh, yeah! I remember meditating in filthy bathroom stalls in punk clubs all over the world. Like on the Death Human tour my first job was always to find a place that I could meditate immediately after I got off of the bus. There were parts of Eastern Europe that were incredibly gnarly and I have these memories where it’s like, ‘I’m going to keep meditating…’ and it became this task to kind of stabilize my mind in what felt like a very challenging environment. You know the thing with this profession is that touring is generally unhealthy. You’re not sleeping well. You’re not in a city for more than two days and the constant movement and the way that you’re being worked…it takes its toll. Add to that the fact that every night’s a party so the booze is flying as well as the drugs. Every city you’re in is an event so it’s really easy to lose balance and get more caught up in the external world of just showing up for an audience every night, (which is a lovely thing to do; it’s a reciprocal thing and it’s beautiful) but at the same time it really is a compromise with a spiritual practice that tends to be more about solitude. I had to really make an effort to find space in order to keep practicing and do that work in those environments. I mean, you’re bringing up things that I haven’t thought about or talked about… I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me about all the shit I had to go through to maintain a meditation practice on the Death Human tour!

FH: Do you think that you were somehow able to cannibalize those challenges and turn them into something that’s provided you with the strength to maintain these practices throughout your life? Was it meaningful or was it more just incidental?

Masvidal: It was definitely meaningful. This was all like seed planting, you know? I feel like it’s all connected. For example, I would say it’s why I was able to finish Ascension Codes in the middle of the incredible hardship of losing my band. And I think, too, the durability of those years… I learned to tolerate a lot more bullshit. When you’re younger you kind of see it all more as an adventure. Whereas, when people get older, they get more stuck in their ways and become less patient. At that point, it was exciting. It was a way of engaging with my environment. And I still do that but I don’t know if I would put myself in some of the situations I was in back then. There were some rough spots, man! Yeah, it’s all connected; that’s the thing. And I don’t know that we can ever really see how these things connect until we can actually look back and go, ‘Oh, okay. I can see how this was related to that. How that behavior is tied to this.’ You know, when Chuck [Schuldiner] got angry… Chuck was generally such a chill stoner dude but when he got triggered—and it was generally something related to the music business or something having to do with a girlfriend—it became a polarizing environment. You were either with him or against him; there was no gray area. You had to completely support him or you were his enemy and it was difficult to navigate that space. For many of us, we would generally just distance ourselves… But I had this spiritual pride as this ‘disciplined, meditating guy,’ thinking that I had some insights. And I did have some… I was essentially raised by therapists. One thing that I didn’t mention was that I came from a pretty traumatic environment. Both of my parents were remarried three times by the time that I was 10 years old so there was a lot of upheaval in the home. I was this high IQ, introverted kid that basically didn’t play with the other kids in the playground because of it. I was just shut down because I was overwhelmed, empathetically absorbing what was happening in my home with my parents and with all the chaos. My mother saw that and she knew that I wasn’t accessible so she put me in therapy when I was five years old (I’ve always joked that I was raised by therapists.) I was constantly in a room with someone observing me or asking me questions and it led to another kind of pathway for me; to being more insightful and trying to understand how your own mind works; accepting that you should stop blaming other people and should take responsibility and become self-reliant… All of these lessons…I think that that was the beauty that came from being in therapy at such a young age. It really helped me to see stuff and got me out of those prisons that we can lock ourselves into, you know? It’s interesting, these Western models combined with the Eastern ones… I really had the merging of those two happening, right? Meditation practice with therapy; they kind of go hand in hand.

A lot of people turn to something that they hope will liberate them without their having to face themselves. That is impossible.

—Chögyam Trungpa

FH: There’s an asceticism that you were describing in terms of your early life and the discipline that you adopted. Is that what attracted you to extreme music? Is it that you saw a foil that you could explore in that way or was there something else entirely about it that caught your interest?

Masvidal: I think initially, the attraction came down to rebellion, right? My older brother was doing the classic rock thing and I just went further with it: Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, Slayer and Metallica… I was drawn to things that pushed the envelope and I think that a lot of that had to do with my personal anger. The aggression spoke to me. And I can still identify with it; I appreciate extremely aggressive music if it’s done well. It’s interesting how it’s evolved, right? It used to be more of a punk aesthetic, it wasn’t about musicianship. It was more about the energy and the vibe of violence and aggression. I remember back in those early days of spiritual practice and I thought I had moved beyond a lot of this, like, ‘I’m not aggressive anymore. I can’t write heavy music anymore.’ And it was like, ‘yeah, right! You’ve barely cracked the surface here!’ The truth is that it’s so subtle, the ways that our rage and aggression appear and I don’t know that we’re ever really finished with it. It’s more that you learn how to work with it. So, the early days were more about connecting to that energy. I mean, the early Cynic demos were almost like punk. They had a crossover vibe and political lyrics and then the more that I got into a spiritual practice and found that it went hand in hand with music, I got turned onto jazz and classical music. But the energy and the aggression of really heavy music spoke to my adolescent rage and my pain and my frustration and how I just felt so disconnected from everybody. It spoke to my isolation and depression. It was real for me and it felt very heavy. All of that stuff kind of blends itself well and that’s the beauty of this kind of music. It becomes an outlet to work through some really intense stuff and if I didn’t have that outlet…I don’t know where else it would’ve gone. The vehicle to process a lot of layered, deep stuff that couldn’t be done with words became music; you could just dig into this gnarly riff and scream! It’s not an accident that I lost my voice. If you listen to Cynic’s ’91 demo, I was in full Chuck mode at that point; just guttural, barbed-wire vocals and it was brutal and it cost me my voice; of course it did! I destroyed my voice; I was raging and pushed it to the very edge until I just couldn’t do it anymore.

You know, I remember that I had an English teacher named Miss Adams and I would give her these poems that I’d written. I remember her telling me, ‘One day you’re going to be writing poems about love. You’re going to be in a different place.’ I was struck by that. Like, ‘really? You think so?’ This is really the birth of Cynic, (when we really found its voice on Focus). Suddenly there was more poetry in what we were doing like Miss Adams predicted. It felt like Cynic had found balance.

FH: Did you feel like you’d lost a part of your identity when you lost your voice? You’re the frontman; it seems like that would’ve been a huge blow. Do you remember what you were feeling at the time?

Masvidal: I remember finally finding my voice because honestly, I could never really growl properly and then by the ’91 demo, at last I hit it. I captured this sound that I was going for. It was like Jeff Becerra and Chuck Schuldiner… this brutal, raging but controlled growl. But of course it wasn’t a technique, I was screaming, you know? So I remember going to a doctor because my throat was really hurting and he just told me, ‘Look, if you keep doing this you’re not going to be able to speak. This is long term damage that you’re doing to your vocal cords.’ I knew at that point that I was going to keep writing the lyrics and so this signifies the emergence of the vocoder. I wasn’t confident as a singer but with the vocoder, I could still be a vocalist. I hid behind this weird keyboard voice sound and it really worked for Cynic because it made us sound more modern. Like, the sound of the band with this vocoder… it was like, ‘this is so interesting!’ It wasn’t quite a human voice, it’s synthesized. So as someone who also enjoys writing, I got to keep being a lyricist. I lost my voice as an aggressive singer but it was ultimately a blessing because I didn’t really identify with singing in that way anymore. I felt like I could still tap into that kind of emotion through my guitar playing, I don’t necessarily have to do it vocally. And thankfully, there’s a lot of people out there with these incredible gifts that can just cop that sound and they just know how to work the technique and it’s almost more of an affectation than like…raging, you know? It’s a different approach, which kind of makes you question where it’s coming from and how authentic it is.

FH: There’s a definite irony there.

Masvidal: Yeah, a lot of the growling vocals that I hear these days are more of an affectation than they are… God, I remember when we were cutting Human, Chuck was already getting tired of growling and this is back in ’91 but he was simultaneously refining his voice. But it wasn’t until he—and mind you, Chuck rarely drank—but he got a couple of beers in him and he just relaxed to the point where that voice came out. It was even more controlled and really powerful but he usually had to loosen up mentally because he was almost timid in regards to what that represented on a personal level. It was interesting to witness that because he could do it so well, you know?

FH: Unquestionably. I was actually the vocalist of a death metal band when I was younger and of course I was wrecking my voice but what I liked about the sound that I was getting was that my voice—even as I was destroying it—was authentic. It would crack and break but I liked that those imperfections demonstrated real emotion. Tapping into the spirit, (and I don’t just mean that as a euphemism) but I think maybe a literal spirit…

Masvidal: Oh, total possession, for sure! Like it literally feels like that… like what the fuck is coming through?! What is this, man?! I remember going to a warehouse party in central Florida where all of those bands were at the time. (We were city kids from Miami but we would go up and hang with the death metal scene up there.) So I went to this party with Chuck. Amon [pre-Deicide] was playing and Xecutioner [pre-Obituary]. I can’t remember who else but it felt like the whole scene was there and I remember hearing [John] Tardy open up his mouth and it was like, ‘What the fuck!’ This guy just took Chuck’s voice to another level! And I really think that in terms of that vocal style, he’s probably at the top of the game. And he still sounds even better live; it’s insane! After all these years he can still exorcise that demon and if you watch him, you can tell that he’s in it. He’s pulling that thing out of his body; it’s really intense for him.

FH: Decibel recently published a book on Obituary [Turned Inside Out: The Official Story of Obituary] and at one point, John Tardy expresses that it can be an emotionally challenging thing to be one of the primary elements that drives people to the band while also being its most divisive element. I get that but at the same time, it makes you wonder… would you really want everyone to be drawn to what you do and to this sound? I mean, what kind of world would that be? Don’t you kind of want to be the entity that the normies are repulsed by and scurry away from?

Masvidal: I know! But that’s always been the thing with death metal, right? I can’t tell you how many times we heard that with Cynic. The whole prog scene would say, ‘I love this band but I can’t do those vocals.’ The moment the growls appeared they were done so we never got to fit in with that more exclusive prog community. I mean, sure, now it’s become more acceptable but back then we felt like we were at the same level as all these other bands but they wouldn’t let us in because of that one element. It’s pretty crazy to see how big some of these bands with that style of vocal have gotten.

FH: Right? That death metal—of all things—could be a viable career. Could you even imagine that back in the day?!

Masvidal: It’s insane! Like Arch Enemy, for example. I mean granted, they’re more of a poppy, thrash-y thing but the vocals are brutal! They’re a huge band that’s doing really, really well and it just goes to show that it’s finally reached that critical mass to where enough people have gotten accustomed to it.

FH: Back to Cynic. The band seemed very unified in terms of its aesthetic. How much did that extend to the spirituality expressed in the lyrics? Was there an alignment there as well or was that part mostly you and the rest of the band just sort of rolled with it?

Masvidal: I think the rest of the band was essentially open and dipping their toes in these concepts but I was the one that was completely absorbed in it, you know? As a band, we would all do psychedelics together and we had some really profound moments and insights. I think each member had their own degree with which they engaged in a spiritual practice or something but yeah, it was definitely me and my world—up to the Robert Venosa connection. His work had been a longstanding childhood fascination and it just blew my mind that we got to use his artwork; he was like this mythical figure to me! I remember when we got signed, Monte [Conner] was like, ‘Okay, you need an album cover,’ so I contacted a publisher that had been putting out his books and postcards and they said, ‘you know, you should just call Robert directly.’ For me this was the blossoming of what would become a spiritual father figure. Venosa held space like this wise elder for young artists—there were a few of us that had this sort of relationship with Robert; he really handpicked who he would work with. I think about all these conversations that we had… He’d lived as a free, liberated artist; I learned so much from him and he gave me a lot of confidence. Robert just saying, ‘Keep going. You got this. You’re good!’ you know? I didn’t have that from my parents; they didn’t understand what the hell I was doing. They were just like, ‘What is this weird shit that you’re making?’ They didn’t go against it but they definitely didn’t understand it. This is why I try to maintain relationships with a lot of young people and creatives. I have a lot of them around me because I know the impact that it had on me and I really feel like it’s my job to show up for other people who are going through that journey as well and do what I can to return the favor.

FH: Sure. Almost like a Bodhisattva.

Masvidal: Yeah! You’re just in service. That’s really what it’s all about at this point.

FH: In its way, Cynic was so audacious that I wouldn’t have presumed you struggled in regard to your confidence and the thought of you struggling in that way while still being as pioneering as you were… that’s even more badass because you’re basically unarmored. I’d just assumed that you went out there with this complete sense of hubris going, ‘This is me. This is what I’m doing and I don’t give a fuck if you don’t understand it.’ But really, it must have been incredibly fucking scary!

Masvidal: Well yeah, it was a little bit… A friend just sent me an interview I did back in the demo era for some documentary about the Florida scene and I see myself talking and immediately recognize all of the protection that I had put up in order to navigate a tough scene. You had to have your guard up. Vulnerability wasn’t honored in metal yet here we were, trying to straddle that line. I can see myself in those old interviews putting on this armor, you know? It was a way of protecting myself because internally I was so insecure—I think the music sort of reflected that. There was a degree of confidence in its execution but lyrically there was also a lot of… I was just trying to be seen, you know? It was entering into spaces that were more vulnerable and real rather than just about being tough or writing about fantasy. It goes hand in hand with a meditation practice, you know? Literally being in the moment and then that moment dissolves… That dream of watching the whole show from a meditative state, that was what really informed our aesthetic. The space that you inhabit when you have a sitting practice…I owe everything to that, (at least I think so.) And of course that gets twined into the music; you have these jazzy, complex harmonic elements and we were also really obsessed with more ethereal music. I was totally into shoegaze and really dreamy, abstract stuff. I remember the first time I heard My Bloody Valentine’s album Loveless, (I think it was while we were on the Death Human tour,) and just going, ‘What the fuck is this?! I love this!’ because it was so wall-of-noise/ambient/ethereal but there were still actual songs underneath it all! I mean, you could break those arrangements down into little piano arrangements and they sound like Beatles songs, but they’re buried in this wall of ethereal noise.

FH: Your speaking of hearing Valentine for the first time and being so attracted to it sparks a lot of joy in me! I can remember these exact points in my life, just walking along, minding my own business and then you catch a melody off of some radio or some device and all of a sudden it’s like falling in love. Like, I have to know this better; what is this? The beautiful moment, (when you look at it from a grander perspective) is that it’s almost like the music doesn’t actually exist if you haven’t ever heard it so it’s like this amazing encounter where the music needed you as well to receive it. It’s like the receiver and the music itself are finally finding counterpoints that are worthy of one another.

Masvidal: Wow! That’s so true because until it’s heard it doesn’t really exist. It’s like…you’re both ‘in on it.’ I’ve never thought about it in that way.

FH: Yeah, and you’re giving it that value so it’s a beautiful moment really for both you and for the music.

Masvidal: Yeah, that is so cool! It’s like my brain just exploded thinking about how these things don’t exist until they’re perceived and then it becomes this space that you cohabitate once you’ve interacted with it and that’s its own thing.

FH: Nice! So, you’ve kind of touched on this already but you mentioned in a previous Decibel interview that you feel that with Cynic in particular, something is channeling you in terms of the writing process. Can you elaborate on that and has that always been the case for Cynic?

Masvidal: Yeah, it’s always been the case that as much as it’s disciplined and mindful and precise and all of these things that go into this high attention to detail—to where it pretty much drives everyone around you crazy… I mean, I basically alienate everyone that I’m working with because they’re just like, ‘Why do you care about that so much?’ We’ve had those moments with every record where people are like, ‘Just stop!’ But I’m finding that the few people that can hold space for that are the people who understand that what’s happening, what’s unfolding isn’t really coming from me. I’m showing up for a process and it’s about trying to capture something and until it’s ready you just keep going, (and honestly, it’s never really ready so it’s this ongoing exercise of just trying to pin something down that’s constantly moving until you can say, ‘Okay, this is close enough. I can stop now.’) I’ve said this before but the process is incredibly personal because it’s emerging from you but it’s simultaneously so impersonal in that every record that Cynic’s made, (and that certainly includes Ascension Codes,) is like… I don’t really know what it is that I’ve made until way after. It can be years before I start to understand. I generally don’t listen to it and the normal course of events [for other bands] is that you’d go tour the record and that hasn’t been Cynic’s thing. It’s just like, it gets made and then it’s gone. For example, I’m about to go shoot a video for Strandberg [Guitars] for an updated model of my guitar that’s in production and I chose a song from Ascension Codes to play so I’m relearning it because I haven’t really played it since it was recorded and I’m like, ‘What the fuck is this part!? Where did this come from?’ It’s like you don’t really understand what happened other than that you were propelled and driven by a process to make something. Then it gets made and, (this is what’s kind of cool about not touring it,) it just becomes this piece of art that you don’t necessarily have to revisit, you can now just move on to the next piece of art, right? So I’ve been more in that mind-space of, ‘just continue creating.’ With touring, you’re not really making anything. To me, it doesn’t feel very creative to tour, it’s more of an interactive performance process and I’d rather make things at this point.

FH: That’s interesting. So it’s like you feel like an MP3 player when you’re up there… I don’t know if you’ve ever talked to Don Anderson of Sculptured. He told me that live performance is his opportunity to really get in touch with his emotions regarding a piece because for him, neither composing nor recording are emotional exercises. So for Don, the live setting is when it finally becomes a living thing that he interacts with. That performance on that night is the one and only expression of that work that will never be exactly repeated again.

Masvidal: Huh. I get that. There is a sacred component to the live performance that’s so unique and special. I mean, you almost can’t compare it but for me, unless there’s a real improvisational aspect to the concert it doesn’t feel… A lot of it, (especially the kind of tours that we were doing) playing night after night you just have your set, you know? You might have one moment where you get to freak out and do something different but for the most part you’re just pumping out those songs night after night and, granted, there’s subtle differences in terms of the details in which you execute things and refine things and maybe a solo was played better this way and I can make this or that better… Live music is its own incredible journey but I feel like it’s probably a deeper one if your thing is largely centered around improvisation, (like you’re a Pat Metheny or something, you know what I mean?) It’s like there’s more subtlety and the artform has that improvisational quality that’s so in the moment but for a lot of bands it’s just so mechanical and frankly, I also have some trauma associated with it. Those last years of touring with Cynic, Sean [Reinert] was so not into it… I mean, he was such a natural and gifted performer. Like, in a live setting, he could just execute things flawlessly and when he was at the top of his game he was the best in the world. Easily. But in those later years when he wasn’t really into it and he didn’t want to play or he didn’t want to play that way… Man, the thing with that kind of playing is that it’s really hard on your body. A prog drummer of that level, it’s something that you peak in your twenties and thirties and afterwards it’s just so physically demanding. It’s like an Olympic sport and after a certain point it just doesn’t work the same way. Sean was at the top of the heap. He was as good as it got but then he just burnt out so on those later tours he began having physical problems. He couldn’t finish sets and stuff. He would never play anybody else’s drum kit, which I understand. He would never make any compromises and that highlights his integrity but simultaneously it made things very difficult because Cynic was never all that big. We couldn’t have these outrageous demands and yet we did! We had them. We were like, ‘if we can’t bring our own drum set and our own this and that then we’re not doing the show. We always had these precedents that made us look like Prima Donnas but it was just the reality in which we were only able to meet these physical demands in a live context.

FH: That’s rough and yet I absolutely understand Sean’s insistence on having his own kit. As a former guitarist, I used to be pretty good (if I do say so) but I could not pick up a strange guitar and execute in a satisfactory manner; certainly not live. It was out of the question because I’d forged a relationship with my instrument. There was faith and a bond between us…including its flaws and my own flaws.

Masvidal: Oh, for sure! And it’s much easier these days, especially for guitar players. Your whole rig is in a petal and your guitar is in your backpack. It’s like you can just do this anywhere but for a drummer it’s different. I saw Atheist a couple of times recently and Kelly’s [Schafer] keeping it going with this young band who are doing an amazing job. And the drummer was playing Suffocation’s drum set and I was saying, ‘Dude, I have to hand it to you…’ and Kelly’s like, ‘Oh, yeah. It’s a thing. I’m playing someone else’s guitar every night,’ you know what I mean? The action’s all wrong and the string gauge and the neck feels weird and he’s making it work!

FH: Yeah! It’s like being expected to lecture in a language that you’re not completely fluent in.

Masvidal: Exactly! But you know, people in the rock and roll business would be like, ‘That’s just paying your dues, man. You can’t be precious about that shit.’ It’s like, ‘Hey, man, if you spent countless hours on an instrument and you developed a high degree of finesse and skill, you deserve to play the instrument that you’re accustomed to,’ you know what I mean? I get it. I get why people would be stubborn about wanting to use their own drum sets.

FH: This will change tack drastically so pardon the digression. I received word just this morning that an old friend of mine had passed away last night due to pancreatic cancer. Wonderful person; just a beautiful man. Since I had the opportunity to talk to you, an intensely spiritual person who’s dealt with more than your fair share of loss, (and also, metal is so fetishistic about death) I wanted to ask: what do you think happens to us after death?

Masvidal: I’m really sorry to hear that and I wish that I could answer that question… I’ve had what people have described as ‘death experiences’ in that I’ve done a lot of high dose psychedelics where you’re completely annihilated. You touch what seems like a death state because your identity is just dissolved, (and I’ve touched this in intense meditation practice too but with a psychedelic you’re sometimes just hurled into it.) So that’s as close as I’ve gotten to it which seems to me that it’s a state of the loss of your identity and the whole attachment to form. This is kind of the goal of all spiritual practices: to access that state where you’re not attached anymore and you really accept how we’re all one thing; kind of one living organism that’s breathing itself but…I don’t really know. I mean, I could give you all these Buddhist explanations and I could tell you what I’ve learned from the Tibetan Book of the Dead about dying practices. I’m fascinated with all of that stuff, (especially the advanced practices like The Rainbow Body technique where it’s like these people have actually mastered death…) The reincarnation model makes a lot of sense to me. It resonates the most in terms of there being this energy that drives the body and (of course) the energy itself doesn’t die; it always exists so when the physical form (the flesh) stops working, that energy has to go somewhere. That makes sense to me. The energy moves and it goes and it inhabits something else; it’s fascinating. We’re just this energetic thing that keeps evolving and it inhabits form and then maybe it stops inhabiting form or it goes into other realms perhaps where there’s no physical forms and it’s something more like ‘light bodies,’ you know? Regardless, this is the beauty of impermanence. None of us can really answer this. It just is. It just happens.

FH: ‘The beauty of impermanence’ is a marvelous turn of phrase. I like that very much.

Masvidal: It’s fascinating when you look at those drawings of reincarnation cycles or those Hindu drawings where we start out as mineral… like, we literally start out as rocks in this realm and then we merge into plant life and then into more sentient life; it’s like these varying degrees of awareness and consciousness that kind of evolve through to how consciousness inhabits form in this realm, you know? They say, (in Buddhism especially) that it’s a real honor to actually be able to acquire a human body. It’s really precious and rare which is why they say ‘Don’t take this for granted. You’re extremely lucky.’ It’s a special thing that you get to have this level of awareness.

FH: Buddhism expresses that we should divorce ourselves from outcome and from expectations, (including hope). But simultaneously, it seems that we do have a goal, (whether it’s to attain enlightenment or else to break the cycle of life, death and rebirth.) How do you reconcile those polarities?

Masvidal: You’re reminding me of a Trungpa lecture that he gave called Journey Without Goal. It basically emphasizes the idea that there is no ‘over there’. The whole point of your practice is about working with your current situation at any given moment and that there’s not a destination. It’s literally always within this moment that the real work exists. That’s the goal. Not to think that there’s something that you have to get over or to complete. It’s not over there and it never was. That’s the paradox; it’s like a riddle. There’s no place to be and when you can relax enough to dissolve into that place you start to realize that, ‘Oh, my god, it’s all just happening. There’s nothing to accomplish.’ I had this insight recently where I thought, ‘Do I actually need to read another book? I’ve been reading so much for so long.’ It’s like, how about just getting to know my own mind, rather than externalizing things and always assuming that the answer’s outside of yourself somewhere? It’s a riddle, right? So yeah, I think those two aims you mentioned are inherently contradictory and the thing that’s so interesting about this path is that it’s not ‘over there.’ It’s always here; that is the practice. To use a pop-culture term, it’s about ‘leaning into it.’ Rather than push away when you feel uncomfortable you just meet it. You sit with all this stuff that you don’t want to sit with and get familiar with all of that stuff. That’s the magic of this moment.

FH: That’s an amazing statement…

Masvidal: Well, it’s just about stopping this struggle and stopping the assumptions that things should be any different than what they are. Stop arguing with the particular version of reality that you’re experiencing and just accept what’s happening fully. Trust and show up and don’t be at war with what’s unfolding. It takes a lot of wisdom and courage to do that. There’s a lot of ‘spiritual materialism,’ especially in the New Age scene…these people actually started to scare me. After I’d gotten deeper into Buddhism I would sometimes go back into these more ‘New Age-y’ scenes and—especially in L.A.—you’d see the whole gamut. You could smell the underlying rage and the unresolved issues from people that are just looking for quick fixes and trying to manipulate their realities to think that they’re somehow enlightened or are at ease with their reality when underneath it all, they’re seething, do you know what I mean? And the thing is, you can’t really manipulate this. It’s not an intellectual process. You have to undo your mind and unlock it. That’s the appeal of a lot of this psychedelic work. It blows you out of those states that you feel like you had agency in. Suddenly, you have nothing to hold onto anymore. It’s terror; there’s no safety net. That was one of Trungpa’s famous quotes, ‘The bad news is, you’re falling through the air, nothing to hang on to, no parachute. The good news is, there’s no ground.’ It’s like you’re in this constant free fall and you never land. That’s the path. You can’t hold on anyway so it’s important to know how to stop trying to. That’s basically a metaphor for a Yoga practice, right?

FH: Yeah, I guess so! So, I had one last question that I really wanted to ask…

Masvidal: For sure!

FH: Do the expectations of your audience—who know you peripherally through your albums and through interviews and the rumor mill—do you feel that those expectations can and perhaps even have chained you to the past? Focus is a great example. Everyone wants to talk about that record but your life is so filled with your work and your other creations… do you feel that there’s an energy attempting to root you to the past?

Masvidal: Oh, absolutely! Are you kidding me?! I mean, jeez. Every other day I get a DM from someone asking what Chuck Schuldiner was like, you know? Especially the metal scene, which for better or for worse, is so nostalgic; I mean, the dedication and the loyalty of the metal scene is really amazing. But at the same time, you’re beholden to your past and they want you to stay the same. It’s the curse, right? Like there’s literally a scene of people who think that we lost our way when we made Focus! They’re all about the demos; that’s it. And then there’s just the Focus people who can’t move past that and now my label president’s telling me that there are people who refuse to listen to the new album because it’s not Sean and Sean. This is the metal scene for you. At the same time, it’s pushing forward and there’s a lot of advancement and open-mindedness and it has come such a long way… But yeah, it’s the most nostalgic genre!

FH: I’d say that we do like to chew on something without ever fully digesting it.

Masvidal: Yeah! We love it! I mean, I’m guilty of it, too. I dig into some of those periods of my life and some of those bands and even just going to see Atheist and then immersing myself afterwards in all of those Piece of Time songs… I was absolutely fan-boying and it felt so good! But that becomes a curse for artists, especially ones that are pushing forward. There were always plenty of bands that played it safe. They found a sound and every record after their first couple of albums becomes a variation of a theme; they never really do anything different. So many bands in this scene are doing that and Cynic’s curse—but then again, I guess it’s not a curse—is that we never wanted to do the same thing. We were always trying to advance forward to uncomfortable places and make something new and rewrite what we’d done before so it was really challenging to the audience because they were like, ‘What’s your sound?’ Now, I’ve always felt like—at the end of the day—there is a sound. There’s a through-line there if you really listen for it but it’s not as obvious as it is with many other bands that kept it safe and consistent. For sure, dude, it happens all the time, especially when you’ve been in it for this long. I started as a teenager and it’s like there’s so much nostalgic references going on constantly that sometimes I just want to disappear. Just ‘get me out of this situation!’ you know? But most of the time I’m trying to meet it, just meet the person where they are. Maybe this or that record from a certain period really meant something to them and they’re always going to be psyched about it and that’s cool; I can relate to that. Just don’t keep me in that prison. Let me be a free, roaming and evolving human that’s shifting and changing just like you hopefully are.

The Beauty of Impermanence

Mindfulness does not mean pushing oneself toward something or hanging on to something. It means allowing oneself to be there in the very moment of what is happening in the living process – and then letting go. —Chögyam Trungpa