When I met first met author Jason Schreurs, through my fellow Decibel scribe, Greg Pratt, I knew him as a writer, an editor/instructor at a Victoria, BC college and a family man. He was part of a friend group in town who would get together occasionally and nerd out playing heavy metal trivia. He, and everyone else in the group, would destroy me, unless the questions involved something like naming the first three Alcatrazz albums or five Rainbow vocalists. Jason knew his shit and was passionate about music. What I didn’t know at the time is that Jason was dealing stuff that even he didn’t understand.

He eventually moved back to his hometown of Powell River, a fairly remote town on BC’s Sunshine Coast, and I heard through our trivia group (which was gathering less and less frequently due to growing families and other grown-up stuff) that he and his wife split up. He started a web magazine that largely focused on music called Rice and Bread with his then girlfriend (now wife) Megan in the mid ’10s, and I sadly lost track of what was going on in his life.

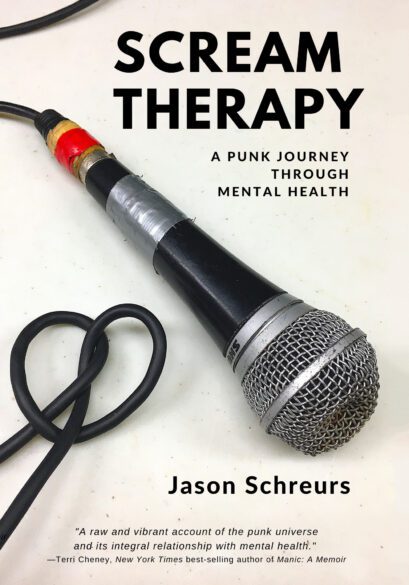

His new book, Scream Therapy: A Punk Journey Through Mental Health (self published through his own Flex Your Head Press), fills in the gaps, as Schreurs had a life-changing reckoning with previously undiagnosed mental health issues that came to head about five years ago, and eventually led him down a productive new path. He’s now a podcaster and author, addressing his own struggles with mental health, and giving a voice to others in the punk scene who have faced the same. Schreurs is currently on a Northwest promotional book tour (dates below), so I hit him up with some questions via email before he hit the road. If you want to get your own copy of the book, go here.

You’ve been involved in the punk and metal scenes in a number of different ways over the years, so what led you to explore mental health issues?

In 2018, I had a psychotic break where I believed my childhood sexual abusers were after me and my son. My family were able to get to me before I carried out any of my blood-thirsty delusions, and they brought me to the hospital where a psychiatrist diagnosed me with bipolar. From there, I began to make sense of what my life had looked like up until that point and what it might look like going forward. I’ve been involved in the punk and metal scenes most of life, but I never stopped to piece together their connection to my and others’ mental health issues. Ramones sang about teenage lobotomies, Black Flag sang about depression, Suicidal Tendencies sang about involuntary hospitalization (plus, the band name says it all). A few of my favorite musicians also lived with bipolar. It was all right there in front me, in the lyrics and the music—punk and mental health had always been linked. So, I began to explore that link by doing the podcast and writing the book.

Can you explain your original concept for starting your Scream Therapy podcast? Was it primarily to connect with and help others, or was it also an opportunity for you to deal with some of your own mental health challenges and traumas?

I started the Scream Therapy podcast because I didn’t know what else to do. The psychotic episode clobbered me like a cinder block. The psychiatrist said it was the same as having a head injury. I couldn’t write anymore, and writing about music was what I had done since I was in high school. I couldn’t get a proper sentence out. I missed interviewing people. Podcasting was my way back in as a writer and journalist. It became of way of finding other people who could tell their lived experiences with mental health, so I could piece together my own. Guests shared their stories with me, and I would support them, and they would do the same for me. I suppose the end game was to inform and educate, but that sounds dull and corny. Let’s just say the podcast is about truth, and questioning, and empowerment.

What did you discover when you started these frank conversations about a topic that is hard for people to talk about?

I’ve had more than 70 guests on the podcast now. I found out that they were willing to talk about their shit without shame, and that these weren’t hard conversation to have under the right circumstances and with the right people. I always ask guests before they come onto the podcast if there’s anything they’d rather not talk about, like things that are off limits, and every single one of them say to ask whatever I want. That’s such a revelation. People are so open about their struggles and their triumphs. I don’t like being called “strong,” or “brave,” or “warriors,” nor do I expect sympathy or want to assume a role of victimhood. Like my guests, I’m just a person who wants to be heard and respected.

I got to know you as a writer, so I’m wondering how therapeutic has writing been, in general, for you?

It definitely calms my mind and shuts out the uncontrollable, racing thoughts that come with bipolar mania. I have to say, it’s very hard to write when I’m depressed, for obvious reasons, but I can dig deep and get it done. When I’m writing, I feel most alive, so it has been a major form of therapy, yes. Writing the Scream Therapy book was a three-year therapy session of piecing together my life, which was a rewarding process and helped me come out the other side with some acceptance and understanding.

Did you ever keep diaries or journals where you addressed or wrote about mental health or past traumas?

No. Not at all. The funny thing is, I had written thousands upon thousands of music reviews, articles, interviews, etc. and when I read back on them now, I can see my journey with bipolar between the lines in my music writing. The phrase “scream therapy” comes up repeatedly, one of my overused phrases like every writer has. I can see the euphoria on the page, like the time I gave St. Anger a four-star rating. St. Fucking Anger. Four stars. I’ll never live that one down. In my published writing, I can see the times when I was really struggling, and the times where I was flourishing. So, I guess the music mags I wrote for and the couple music websites I did were my journals and diaries?

Describe your experience playing music? Has this been an emotional as well as a creative outlet?

When I’m pounding on a guitar or screaming into a microphone, I go to a difference place almost immediately. A switch goes off and, at the best of times, I’m in a state of flow. At the worst of times, usually when I was screaming, I would enter a world that was dangerous, and exciting, and threatening, and glorious all at once. It manifested in self-harm onstage, a way of punishing myself. I was often purging rage against my childhood abusers and the sexual predators in the punk and metal scenes. But there was joy and love in there as well, as I fought to break free of a monster of my own making. It was fucking weird.

When it came to writing your book, did you have a pretty good sense of how you would bring together serious mental health discussions with the punk/metal world you grew up loving and writing about?

I had very little idea of where it would go, honestly. I was researching and doing my interviews for the podcast, and learning from mental health pros who were also punks, but I knew I had to tell my story, first and foremost. When I sat down to write, what came out was something I could have never planned for or predicted. The keyboard was a conduit for my journey, good and bad.

Did the journey of writing the book provide some surprises that you hadn’t anticipated regarding the topic you’re addressing?

Yes, all kinds of surprises. For one, it made me question the language around mental health. That terms like “disorder” and “illness” only serve to hold down people living with mental health conditions. That the term “breakdown” implies a person is reduced to rubble and needs to build themselves back up, a false narrative that I’ve been prone to believe myself. I much prefer the term “mental health crisis,” which implies that I have control over my health, and this is a time of crisis, but it doesn’t have to hold me down. Another one is the idea of “recovery.” Recovery sounds like I’m trying to get back to a place where I was before, but what if that place was awful, and destructive, and self-sabotaging? Why would I want to recover and go back to that? I’d much rather move forward on a different path and find a new way that makes me feel most alive.

Is it your hope that Scream Therapy is a conversation starter for people who may have had similar experiences as you and others in the book but haven’t maybe addressed or acknowledged them?

It would be amazing if that would happen. The book embraces self-empowerment, and learning, and resisting the dominant ideas of psychiatric health and what community and identity looks like. Those topics can bring up some important questions. The book also provides a perspective on punk rock maybe a lot of people haven’t thought of before—that punk rock is love, simple as that. I don’t think I wrote the book as a conversation starter, at least not consciously. Ultimately, I wrote it for three reasons. One, it felt like my survival depended on it, like if I didn’t write this book, what else could I do to feel alive—to keep myself alive? Two, I wanted to do justice to the people who were generous enough to share their stories with me. Three, I’m a writer, I was practicing my craft, I was enjoying the process, I was creating.

What would your positive mental health, Scream Therapy, Spotify playlist look like?

Oh man… where do I start? Some of the bands I look to for inspiration in the book are Hot Water Music, Fugazi, Amygdala, Jawbreaker, Planes Mistaken for Stars, Heavens to Betsy, Converge, Black Sabbath (my gateway to thrash metal, which was my gateway to punk rock), and definitely the Thrasher Skate Rock tapes from the late ‘80s with bands like the Accused, Corrosion of Conformity, Septic Death, and Beyond Possession. But the playlist would be endless, really.

How is your mental health these days, and what are some of your own strategies for staying mentally healthy?

Steady as she goes. My bipolar mood episodes aren’t nearly as long or intense as they were after my diagnosis in 2018. They kept being shitty into 2020, around COVID times. Not to make light of a horrible few years for so many people, but I truly believe COVID is why I’m stable now. Everything slowed right down, I established solid routines and sleep and meal hygiene, and I wasn’t staying out until 2 am for seven-band death metal shows. Seriously though, as one of the elders in my the bipolar support group I facilitate says, “A boring life is a good life.” I wouldn’t go that far, but he’s onto something.