Doug Moore knows a thing or two about extreme metal vocals: after all, the man sings for noise-metal racketeers Pyrrhon (whose Abscess Time from last June is still bending minds) and DM heavy hitters Glorious Depravity, whose most recent album, Ageless Violence, dropped on November 27. I mean, then there are his other bands: doom/deathsters Weeping Sores, black/death trio Seputus… I’m not really sure how he had time to deal with our request to spout off for a while about the five heavy albums that changed his life, but here we are.

“A lot of the albums that make up my primal metal influences are super famous, and nobody needs to hear how great Master of Puppets and Covenant are again,” says Moore. “Here are a few slightly less obvious albums that changed the way I think about life and music.”

Nile – Black Seeds of Vengeance (2000)

Black Seeds isn’t the first death metal album that really captured me, or the one that influenced my own shit the most, but it’s the one that drove home how big of a role death metal was going to play in my life. When I first came across it around age 15, I considered it more or less a joke. And like so much death metal, it is pretty absurd in many ways: Derek Roddy’s strobing blasts; Karl and Dallas’s mile-a-minute tandem gurgles; Bob Moore’s murky, fecal production; the dorky lyrical theme and accompanying exoticist musical dressing; and especially the insane song titles. During my first month in possession of Black Seeds of Vengeance, I would often play snippets of it for friends or read out titles like “Libation Unto the Shades Who Lurk in the Shadows of the Temple of Anhur” to get laughs out of them. But before long, playing it for friends as a joke on occasion became listening to it on my own all the time, because as it turns out, Nile rips extremely hard. Black Seeds taught me that the absurdity of death metal is a feature, not a bug. Even today, I consider it a good sign when a new DM album can make me laugh.

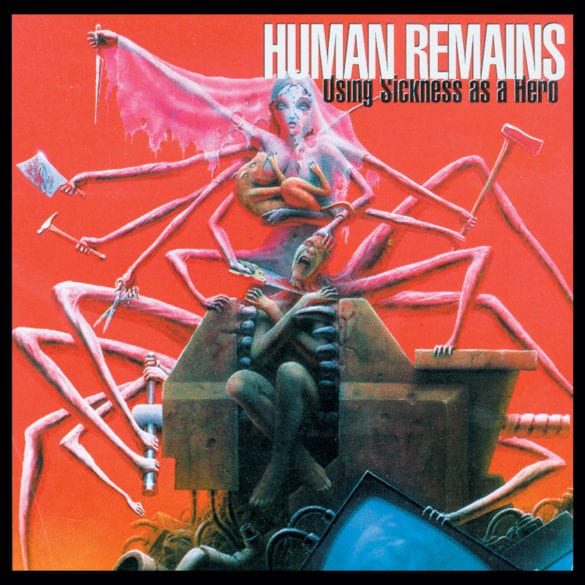

Human Remains – Using Sickness as a Hero (1996)

Not long after my come-to-Satan moment with Nile, I blind-bought the 2002 Relapse reissue of the Human Remains discography, mostly because I had started getting into some other Dave Witte bands and thought he was a cool drummer. I wasn’t ready for the scuzziness of the early material on the comp yet, but Using Sickness as a Hero blew me away. Even in the early ’00s, when metal/hardcore hybrids had become commonplace, there was really nothing quite like Human Remains around. They had no respect for the supposedly important distinctions between various types of extreme underground guitar music, and plainly only cared about fucking you up. But they were playful about it, too; they’d flip from Looney Tunes guitar noises to blasts and back within a span of a few seconds. Using Sickness is only 17 minutes long, but it showed me that it’s better not to care about other people’s ideas regarding what music should be. For such a brutal album, it feels incredibly free and explorative—qualities that a lot of self-serious metal chuds didn’t appreciate then and still don’t today. But as the sample from “Human” puts it: well, who gives a fuck what you think?

Slint – Spiderland (1991)

I think I first came across Spiderland via a passing mention in a review of Calculating Infinity, of all places, circa 2002 or 2003. At the time, the only thing I cared about was finding the next heaviest thing out there. Spiderland stopped me in my tracks anyway. It wasn’t fast or loud, but it was clearly heavy in some eerie, intimate way that I had never encountered before. The music seemed to have emerged whole from the mind of some ruminating shut-in, a hermit somehow projecting himself into the limbs and throats of the four puckish kids adrift on the album jacket. The fact that the band had dissolved messily after recording such a masterpiece, leaving their promise unfulfilled, thickened the air of mystery and tragedy around it. More than any other album, Spiderland taught me that the nebulous musical quality of “heaviness”—perhaps better thought of as intensity or severity—doesn’t necessarily depend on loud volumes or rhythmic density. Quiet expressions of anguish can crush just as easily as any kill riff.

Cursed – II (2005)

Near the end of high school, I started to realize that my musical future lay in vocals (as I sucked at guitar and drums, despite my best efforts). Compelling lyrics are pretty thin on the ground in metal and hardcore, so the handful of sharp lyricists I came across at the time seemed like gods to me. My own later efforts probably owe the most to Chris Colohan’s lyrics on this album. Unlike the shallow sloganeering of most overtly political heavy music, Colohan’s bitter tales of humans being ground to pulp in post-industrial Toronto seemed to capture something profound about the way political evil works in the everyday life: as a creeping background process that sets the terms for reality without clearly announcing itself. I was particularly struck by the way he would creatively repurpose commonplace, clichéd phrases to show how sinister they really are—a trick I have ripped off many times. And as good as Colohan is as a singer and writer on this album, the band is right there with him. II should be considered a top-10 metallic hardcore classic. I remember going for a lot of lonely runs at night while listening to this album back then, and feeling that something was following me, just out of view.

Anaal Nathrakh – Eschaton (2006)

I had been a fan of Anaal Nathrakh for a bit when this album came out, so it didn’t feel like as much of an epochal encounter when I first heard it as the rest of the albums on this list did. Nonetheless, it inspired me to go all-out as a vocalist and push my instrument to its limits in a way that no other album has. Dave Hunt was a monster on the Anaal Nathrakh and Mistress releases prior to Eschaton, but on this album he absolutely took over, dominating in about seven different registers and outshining a set of Mick Kenney instrumentals that are themselves unfairly stacked. As wild as Hunt’s performance gets, it’s clear that he put a ton of thought into his arrangements, which often make it sound like there’s a whole gang of DH clones screeching at you. (You can tell that there’s a nerd spewing all that venom by sourcing nearly all of this album’s song titles and audible lyrics to various hifalutin’ intellectual sources.) A great deal of extreme metal—even the good stuff!—treats vocals as an afterthought to the main event; this monument to ambition and athleticism in the vocal department sounded like a call to arms for me.