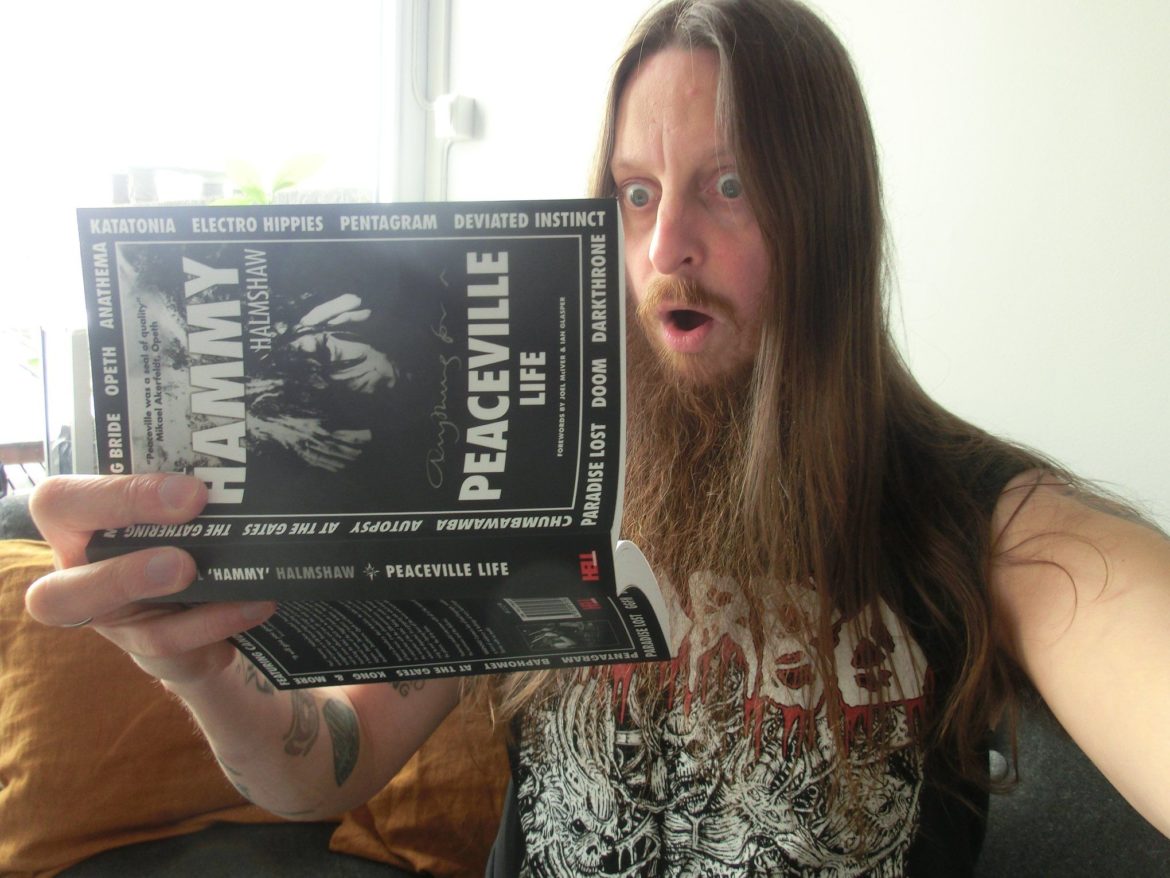

Few record labels—if any—have done more to propel underground metal forward than the U.K.’s Peaceville Records. From Autopsy’s Severed Survival to Paradise Lost’s Gothic, through Darkthrone’s A Blaze in the Northern Sky and My Dying Bride’s Turn Loose the Swans, Peaceville’s back catalog is littered with Decibel Hall of Fame-inducted subgenre landmarks that have soundtracked nearly three decades of the miserable lives of multiple Decibel staffers.

Founded in 1983 by Paul “Hammy” Halmshaw as a cassette label specializing in the U.K.’s then-burgeoning archo punk scene, Peaceville moved onto flexi discs and 7-inch singles by 1987. A year later, full records from crust heroes Doom and Deviated Instinct appeared, soon followed by debuts from Autopsy, Paradise Lost, Darkthrone, which changed not only the direction of the label, but the fate of death metal, doom metal and black metal, respectively. At the Gates, Anathema and Pentagram followed. Katatonia signed to Peaceville mid-career and never left, while their musical brothers in Opeth signed for one record and were immediately poached by Peaceville’s then parent company Music for Nations and jettisoned into mega-stardom.

Halmshaw details his interactions with these legendary acts and countless others in the recently published extended edition of his Peaceville Life book. As a man who actually owns Electro Hippies, GGFH and Sonic Violence albums, I felt qualified to ask him the following questions.

Writing a book sure sucks, doesn’t it? It’s not all terrible, though. Apart from actually finishing the thing, what was the most rewarding part of the process for you?

Hammy: Ha-ha! Yes, it does suck in some ways. I mean, endlessly proof reading 85,000 words for instance. It’s a ball buster, no doubt about it. But also, it has, thankfully, been one of the most directly rewarding things I’ve ever done. I don’t think anyone—bands included—knew what had gone on at the end of (our tenure at) the label. At the outset, almost everyone involved was wary of what I was going to write. I do know rather a lot of sensitive things about some people, so it was understandable. However, they have all loved the finished thing and it has kind-of nicely rounded off our relationships. We didn’t sell out and go live on a yacht, we were emotionally destroyed—but no one really knew that.

Were there any other music biographies that inspired you from the onset?

Yes, there was one really big one: Footnote by Boff Whalley from Chumbawamba. I’d started writing my book as soon as we’d left the label, some 12 years ago now—as a kind of cathartic act, to expunge it—but it never found its flow. Then my mother died, and I shelved the idea for a long time. I read Boff’s book and was blown away by the approach. It’s a very honest—bare, even—book but is very warm and friendly with it. When I went back to my notes I found that by employing that same tone, everything I’d written suddenly took on its own life. That, more than anything, helped me to get it over the first big hurdle. How to make it honest without being horrible.

You reveal a lot of your personal background at the start of the book, as well as addressing what was happening throughout your personal life as the story of the label’s ascent unfolds. This is at odds with the persona of “Hammy the enigma,” in which you shrouded yourself in mystery through much of the ’90s. Obviously, the bands knew you, but apart from that, you were a more mysterious figure compared to most label bosses. Are you really an introvert? And if so, was it difficult to open up like this in the form of a book?

I grew up on Crass records with healthy doses of the Residents and The KLF thrown in. All “bands” that shrouded themselves in secrecy and created an enigma just by being secret. As we were just one guy in a social housing bedroom in West Yorkshire, that approach suited us brilliantly. I had to create the idea of something far bigger than it actually was. Plus, as a massive stoner (which was, and still is, illegal in the U.K.) it meant that our offices were always locked with the curtains on, so I could build endless joints in peace. Anything for a peaceful life…

I am chronically shy though, not an introvert as such, but I really do prefer writing to talking and that’s where the book came in. To me, it wasn’t so much about giving away all my secrets as recounting how one seemingly unconnected act became the stepping stone to another and another which, by some quirk of fate, led to becoming one of the hottest labels on the planet for a short while. It was probably as important for me to join the dots as it was anyone else. Only when you stand back do you see that all the parts made a whole which was bigger than the sum of its parts.

No label/artist relationship is perfect, but Peaceville seems to have a much better track record with its earliest breakthrough acts than another prominent British label of the era that I can think of. To what do you attribute this?

I think that my main strength was not having an agenda. I think all the early bands knew that we were making it up as we went along. That I wasn’t a “career obsessive”—I was just a young kid myself and not much older than the bands. It was a lot safer for them to go with me than risk everything on some “big” label that might start messing with their look, or sound, or songwriting. I gave them all freedom—to do exactly what they wanted (for better or worse). Plus, I also think that they trusted me as an individual and I don’t think I let many people down. Certainly not intentionally. I’m way too shambolic—stoned?—to be an evil capitalist.

In 1995 you famously did a deal with then U.K. powerhouse Music for Nations that essentially gave them a stake in Peaceville and forever changed the course of the label. 23 years later, any regrets?

No, none. How can I when I’ve had such an interesting ride? I had no idea how to run a business, so I probably didn’t look at the downsides as much as I should have—at the beginning, but what I hope people will get from the book is that I didn’t feel like I was blessed with too many choices at critical times. I went with my gut instinct and always reacted in the way that would best protect the catalogue—as I knew that was the asset, not any band on its own. Who was to know that within two years MFN would be gone (in many ways)? They were dark days, but I learned a lot. Hindsight is just there to taunt us, you couldn’t have changed anything—or you would have.

I’m not going to ask you to pick your favorite release from Peaceville (because I don’t think I could even pick one), so let’s do something different: Please give me your favorite Peaceville record from these three bands who splintered off from other legendary bands: The Blood Divine, Blackstar or The Great Deceiver.

The Great Deceiver, Terra Incognito—criminally overlooked. A great record.

Obviously, the landscape of the music industry has changed dramatically since you first entered it (hell, it’s changed even more dramatically since you exited it in 2006!), but do you ever toy with the idea of getting back into it? Maybe even come first circle and do a cassette or flexi label? Or am I fucking crazy for even asking?

That’s not as crazy as it first seems. The book is a part of that process I believe. The fact that I’ve done everything myself – from writing to publishing to mailing them out—is exactly that rounding of a circle. It’s the first time I’ve been totally independent since the cassettes and singles. Plus, I’m loving every minute again, being directly in touch with people. The Hell Segundo imprint is up and running for more projects—they just won’t be metal records, that’s all. They may not be music related even. Nothing is set in stone, but there are ideas… and I’m dangerous with ideas.

Order a copy of A Peaceville Life here.