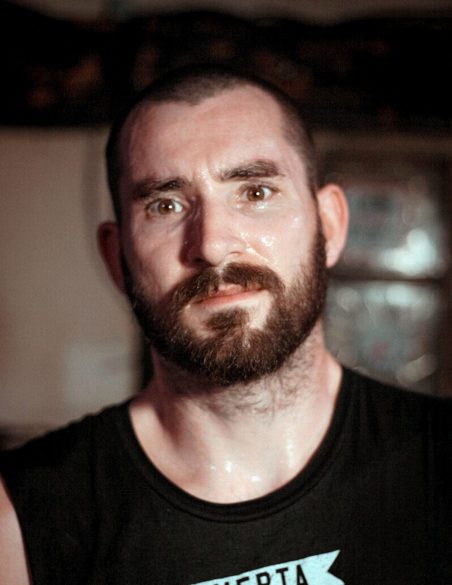

If you’re tempted to fuck with Mike Justian’s resume, you probably should reconsider:

Trap Them. The Red Chord. 108. Earth Crisis. Shai Hulud. Backstabbers, Inc.

Most recently, the legend-in-the-making can be found manning the kit for Madball — and his signature blend of deft precision and primal brutality is all over For the Cause, an album Decibel described as “not only the most diverse, consistently interesting offering” of the New York City Hardcore institution’s storied career, but perhaps “the band’s best record, period.”

Trust us, it’s a gnarly hardcore beast that’s gonna turn heads and blow minds.

And this next in a long line of stellar performances seemed as good an excuse as any to ring up Justian for a chat about his musical background, rise to the top of the underground, and what it’s like to have the heroes of your youth become peers.

The man did not disappoint…

So the first time I saw you perform, many years ago now, you were playing guitar for Backstabbers, Inc. And then shortly after that I got a copy of Fused Together in Revolving Doors — which is such a wonderfully insane record — and had this realization you were the same guy, only delivering this virtuoso drum performance. In the years since, you’ve obviously become a go-to drummer for all of these seminal bands, but just because of my own background with your music I’m curious about how you developed as a musician.

Well, drumming absolutely came first and most naturally to me. I mean, from very early on, I was flipping laundry baskets over and hitting them with wooden spoons — things like that.

Was there a particular song or musician that inspired you to do that?

No, not really. I mean, my dad was a musician, so it didn’t come out of nowhere. I didn’t just start arbitrarily beating on laundry baskets. The connection is my dad, and my mom as well,

but my dad was an actual professional musician. And when he would go and do gigs, I would kind of engineer my own little gig in the living room, where I would flip the laundry baskets over and just start playing. I would simulate, in my mind, the experience of playing a show.

So, did your dad play drums or was he…

His path was basically the exact opposite of mine — he started on drums, but then really found his calling as a singer and guitar player. For me, drumming was absolutely my calling. Guitar was something that I did just out of necessity. I would have these song ideas and it was just more efficient and economical, I suppose, to try to learn how to play guitar, in order to put these ideas together, without having to express them to other people with my very limited musical vocabulary. At that point I didn’t want to be at the mercy of other people or at the mercy of my lack of ability.

Considering all that, did your guitar playing wind up having a percussive quality?

Not at first. I started out just sort of jabbing away at guitar strings. If there was any sort of rhythmical construct to it, it certainly wasn’t the intention. My guitar playing wasn’t very deliberate, initially, and then once I actually started getting into a situation where I could formulate chords and progressions and whatnot, it sort of became a style of almost drumming through a riff, to emphasize the drums.

Which came first for you – metal or hardcore?

Hardcore. In a very brief period of time, I went from listening to Nirvana to listening to Sick of It All. And then a little bit later came metal, particularly death metal. But, you know, I didn’t really understand that there was any sort of distinction between a hardcore kid and a heavy metal kid, or anything like that. To me it was just all counterculture music — music that appealed to the sensibilities of social outcasts around the world. That was the aspect of it that had the most resounding effect on me.

Where did you grow up?

In a city north of Boston called Lynn, Massachusetts… Which certainly reinforced my interest in heavy music, because it really also was the golden age of music venues in Boston. You still had The Rat. You had all the different clubs on Lansdowne Street, which have almost all been systematically overtaken by House of Blues. The Middle East is still around, which is cool, but back then you had this incredible set of venues and clubs, so I was going to shows at least three times a week, at one point.

Right, and that was an era in Boston in which you really could go to an indie rock show, a metal show and then a hardcore show — often all on the same night. Did that access to such a vital, diverse mix of bands have an impact?

Yeah, that coupled with the fact that it was really cheap. Shows were a much more affordable enterprise back then. Even public transport was really cheap. Now it seems like the price just to get to a show is more than the price of what a show used to be.

It seems like most people who get into hardcore, if they have any musical inclination at all, have the urge to start a band. Is that what happened in your case? You just loved this music and you wanted to play it?

Yeah, I wonder how active of a love affair it was. I think that, for me, it was just the fact that it was this fairly primitive, kind of like cathartic, visceral musical experience. And then that, coupled with the fact that it spoke a lot about street values and sort of like street sensibilities, and that started to be something that I could identify with, living where I lived. I guess the music was just kind of the reflection of that, this sort of blistering, sort of rhythmically pounding musical force.

That makes sense, actually, because you’ve covered a lot of ground stylistically and sub-genre-wise throughout your career, but the thread running through the vast majority of the bands you’ve played in is less about the style of riffs, but instead this very visceral, authentic attack. Does that sound at all accurate?

Yeah, that’s definitely accurate. I’ve always been fairly multifaceted in terms of the different kinds of music that appeal to me. The other thing that’s always been important to me is to make music that is devoid of pretense.

As a longtime fan of metal and hardcore, it must be gratifying to have been tapped to play in so many of groundbreaking bands of the genre.

It’s surreal, actually. These are bands that, harking back to what I was saying about going to shows three times a week, very often those shows included seeing some of the bands that I ended up playing for. I saw Madball for the first time at The Rat on their Set It Off tour. I’d seen them many times after that. So being in Madball is nothing short of amazing. Then having also played drums for Earth Crisis. I still occasionally play shows with 108. So, yeah, it’s somewhat dream-like, to be honest.

Let’s zero in on Madball, since that’s the reason for our chat today. Do you remember the first time you heard the band?

Definitely. My first encounter with their music was a radio station that had a show every Sunday, that focused on agitating, heavy music — hardcore punk, stuff like that. And one Sunday the DJ premiered “Down By Law.” At that time, I hadn’t really heard anything quite like it. I’d heard Sick of It All and some other hardcore bands, but most of that stuff I’d heard focused more on the fast and pounding end of things. It didn’t really utilize as many of the power pocket kinds of rhythmic approaches that Madball did. It was insanely innovative. Now you almost don’t have a hardcore song that doesn’t have a quote/unquote “breakdown” and that’s largely due to the funk and hip hop influence Madball brought into hardcore.

Now, sometime after that, as you already mentioned, you saw the band at the Rat. Which I’m sure was a heightened experience.

It was a much more terrifying experience! I mean, the show at The Rat, it was like a can of sardines, and then when they started playing, it was like Vesuvius erupting.

Did that explosion appeal to you?

Yeah, of course. It added a new layer to the onion, I suppose, and that layer was a lot juicier and spicier.

How did you end up playing with the band? Obviously, by the time you got the call you had an impressive resume. I imagine, at that particular point in time, they were looking also for a personality fit…

I had toured extensively with other bands and we had crossed paths and became friendly. The time came where they needed a drummer and I needed a band, and it just sort of worked out like that. It was a fairly streamlined, organic process. I didn’t audition or anything like that. I filled in for a couple of tours—which, I suppose, was something of an audition. They weren’t going to just jump to the conclusion that I should join the band, because they had gone through a succession of drummers at that point that had not really worked out. So they were somewhat cautious, and understandably so.

Did you feel like your style really clicked into the Madball machine?

Yeah. I’ve always kind of viewed myself as a power pocket drummer, primarily. Some of the other things that I did beyond that — say, a blast beat or something in 7/8 time or whatever — were just a matter of serving the interests of a particular song. Primarily, though, I’m a power hitter, and I’m happy to lay in the pocket and just flat out get into a groove.

Which is sort of funny, because I think that there was some reservation from them — and perhaps even some people on the Madball periphery who were aware of some of the bands that I’d played for — that I’d try to wave some crazy wand over their music and change things. In reality, I grew up on this stuff. I have way too much respect for Madball to do anything like that. The truth is, I totally understand the beauty of what Madball does, and it actually really lends itself to the way that I play.

So you arrive in the band, do the Hardcore Lives, which is a very good Madball record. But — no disrespect to it — For the Cause feels like it’s on another level. It feels like a great record. Is that just an outsider take? Or did you feel a difference between the two?

Well, the writing process was a little bit different. It was different in that we were short a guitar player, so this record came together really with Hoya playing guitar. And then me on drums, of course, and Freddy overseeing the whole process, which ultimately worked. It took a little bit more time, I think, for Hoya to get more comfortable and acclimated to playing guitar, but once his hands freed up, it came pretty easily. Hoya has just been a geyser of creativity with music and song ideas, which you, of course, hear on this record. There’s a lot of music that is quite a bit different from previous Madball albums.

Did having to deal with that sort of change-up liberate the band at all?

I think so. But, look, I don’t think at this point Madball has anything to prove. Madball doesn’t have to out-Madball Madball. I mean, I think it’s appropriate to move forward, as it is with any musical endeavor or artistic endeavor. It’s got to move in a direction.

What was Matt Henderson’s role, then? Studio tracking?

Yeah, Matt tracked all the guitars on the album, and that was pretty much the extent of his role. He made a couple of suggestions with a couple of the songs, but his primary service to the band was tracking guitars, which he did in a way that only Matt Henderson can perform.Those are Hoya’s riffs and Hoya’s songs, but Matt just has such a singular way of playing, and approaching riffs, and interpreting riffs. His tone is so solid and so specific to Matt Henderson.It was really great to have him participate and track this thing.

Then there’s Freddy’s performance, which is one for the ages, I think. He kills on the classic Madball vocal end, but is also really adventurous in his approach on some of this stuff. People are going to be be surprised.

Yeah, Hoya brought all of these new and interesting riffs and ideas to the table — stuff that was sometimes pretty different from the standard Madball concept. And a lot of those ideas were actually encouraged by Freddy. He wanted to explore those ideas and see if we could turn them into bona fide Madball songs. So Hoya came into this with the intention of stepping his game up, and I think that Freddy saw the potential and — like myself — took it as an opportunity to try to really step his game up as well. And he certainly did that.

I don’t have quite as proactive a role in Madball, I would say, as in some other bands I’ve played in. But that’s the dynamic that works and makes the most sense. Freddy and Hoya are so proactive and constantly inspired. Hoya, especially, had a pretty vivid concept, musically, for this album. That was reinforced by Freddy. I really just made it my mission to just try to understand it and interpret it on drums, as best as I can.

Do you feel like you’ve learned new things, playing in Madball?

Oh, absolutely. As a drummer, one of the best things that you can do — one of the most singularly important attributes of a good drummer — is developing the ability to keep time. Playing for Madball has really taught me the value of having a pretty solid internal metronome. Our tempos can change from show to show based on the environment and the sort of reciprocating experience of the crowd. Or if there’s a lack of reciprocation from the crowd, that can tip the tempos in a different direction. Having to pay attention to that has taught me a lot about how to change the tempo fairly quickly and lock into it whenever the moment calls for it.

I’ve personally have seen you perform in some pretty gritty, bare bones venues. And from there you’ve gone on to perform across the globe and play on several modern classics of heavy music. Do you think that trajectory says anything about the value of vision and perseverance?

Yeah, I’ve always maintained that perseverance is the essence of success. Success itself, of course, encompasses a great degree of subjectivity. My interpretation of success is going to be vastly different from someone else’s. I’m able to make what appears to be some semblance of a living playing hardcore music and traveling the world — that, to me, is unbelievable success. I’m an extraordinarily lucky person.