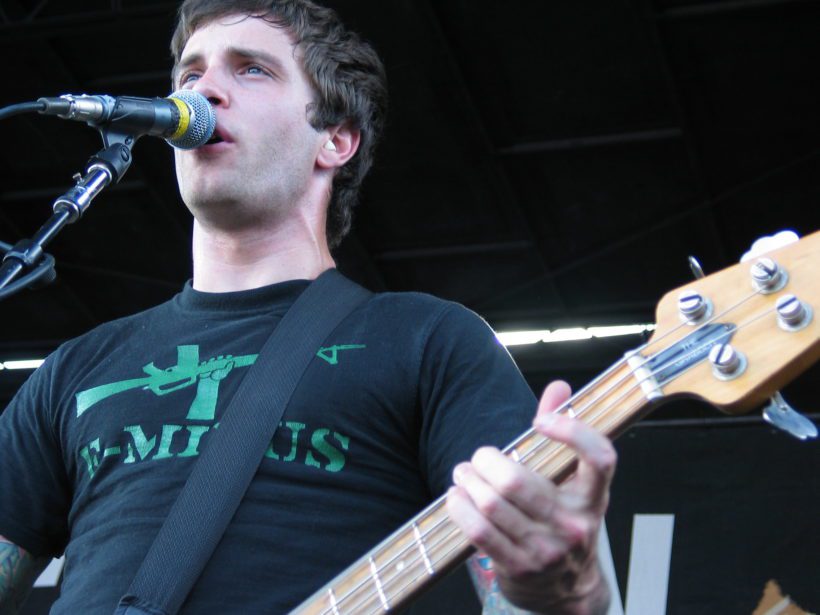

Caleb Scofield is onstage in Bonner Springs, KS. He’s wearing an army green t-shirt and jeans. He’s belting out the lyrics to “Moral Eclipse” from Until Your Heart Stops. His voice is a like a blast furnace. His bass tone is locked in somewhere between earthquake and tsunami. It’s July 8, 2003. It’s sweltering. Feel the heat coming off the asphalt. See the sweat dripping down his face. It’s the purest kind of sweat: The kind that comes from fulfilling one’s dreams.

At this moment in time, Cave In have put out two of the greatest albums ever made by humans: Jupiter and Until Your Heart Stops. They’re on a major label. They’re playing the second stage on Lollapalooza. I’m there snapping photos. It’s the first time Cave In have played anything from Until Your Heart Stops in years. The big difference? Caleb is handling the vocals, so Brodsky can preserve his pipes for the prettier stuff.

Caleb roars. His bass is attached to its strap by electrical tape. The song ends. The crowd goes apeshit. He flashes that million-dollar smile.

A week later, we end up at a party in Cincinnati. Caleb is fairly new to partying: It doesn’t take much to get him lit up like a Christmas tree. We hoof it back over the bridge to our hotel in Covington, Kentucky. I drop him off at the room he’s sharing with the other Cave In dudes. The last thing I see as I walk out the door is Caleb jumping up and down on a bed. The Cave In dudes are half amused and half wondering how they’re going to get any sleep with a maniac bouncing off the walls. When I get back to my room, the phone rings almost immediately. It’s Brodsky: “Hey, dude. Thanks for dropping Caleb off. Can you come back and get him?”

Fast-forward a couple of years. We’re in Caleb’s backyard in Los Angeles. It’s summer again. We’re drinking beer. The word “straightedge” is tattooed across his back in huge letters. I ask when he’s going to get it covered up. “Never,” he deadpans. “I was stupid enough to get it, so now I have to live with it.”

He flashes that million-dollar smile.

Around this time, Caleb changes my daily behavior on a permanent basis. Someone lifts his pin number off a self-serve pump. They drain his account. Since the day he told me, I haven’t entered my pin number into anything except the ATMs at my own bank. That was probably 13 years ago.

In 2007, Caleb and his wife Jen have a baby boy: Desmond. They move back to the East Coast. They have a little girl: Sydney. I don’t see Caleb as much, but when I do it’s like no time has passed. We joke. We laugh. He shows me his new tattoo. He flashes that million-dollar smile.

In late 2012, my band Ides of Gemini plays two shows with Old Man Gloom: Los Angeles and San Diego. After the second show, we exchange band shirts. Caleb wears his onstage the very next night.

Time passes. Life takes over. I don’t stay in touch as much as I should. I start playing bass in a couple of bands. I don’t realize it at the time, but I’ve adopted Caleb’s instrument. Maybe it means something. Probably it doesn’t. Either way, Caleb keeps making awesome records with Old Man Gloom. He tours. He crushes. He puts his entire being into the music. He delivers the fucking goods.

On March 28th, 2018, he’s killed in a terrible accident. Just like that, he’s gone. When I find out, I’m doing my radio show—live on the air. I can’t finish the show. I leave the building. The producers swoop in with some pre-recorded whatever. They don’t even question my departure. They just do what they have to do. Which is exactly what Caleb would have done.

I go home and bawl my eyes out. I exchange stunned messages with his bandmates in Cave In and Old Man Gloom. I read an account of the accident in his local paper. I see the photo of his burnt-out truck. I wish I hadn’t.

The next day, I listen to Jupiter over and over again. It’s as amazing as it was the day it came out—18 years ago. But now it’s fucking devastating. I find myself fixating on certain lyrics—like the all-too-obvious, “And you’re so lucky to be alive…” from “Big Riff.” When I was younger, I thought that line was a little cheesy. I don’t anymore.

Sometime around the fifth or sixth spin, I decide that I’m wallowing. Caleb wouldn’t want me to wallow. He’d tell me to buck up. He’d remind me that life isn’t always fair. He’d tell me to stop being a fucking baby and get on with it.

And I will—but not today. Not when my friend is barely in his grave. Not when his family, friends and bandmates are suddenly poorer for his absence. Not when everyone he touched with his music is suddenly poorer for his absence.

Just like that, he’s gone.

Here’s one of those awful lists that make death so much worse: Caleb leaves behind his wife, Jen. Their two children, Sydney and Desmond. His brother Kyle. His mother Faith. His bandmates in Cave In, Old Man Gloom and Zozobra. Friends. Extended family. Countless fans around the globe. People he connected with through music.

Just like that, he’s gone.

I don’t know how to end this—mostly because of the finality that an ending implies. I don’t have any great insights or wisdom that will ease the pain of Caleb’s departure for anyone.

I do know this, though: I’m going to listen to those records until the day I join him in the great beyond.