Each year during the drive down to Maryland Deathfest, the in-car topic inevitably turns to the merch purchases and record shopping poised to send our traveling collective to the poor house. Being an incorrigible brat, I usually interject with an oppositional diatribe about instead scouring local bookstores and scooping up as much reading material as is available, followed by a sardonic, “Some days, I’d rather read about metal than listen to it.” It’s a comment usually greeted with a mix of polite laughter and here-he-goes-again eye-rolling, but it’s what you do when you want to rest your ear holes, but can’t get metal off the brain. And Tom Gabriel Fischer is with me: “I completely understand this feeling. I have it sometimes, too.”

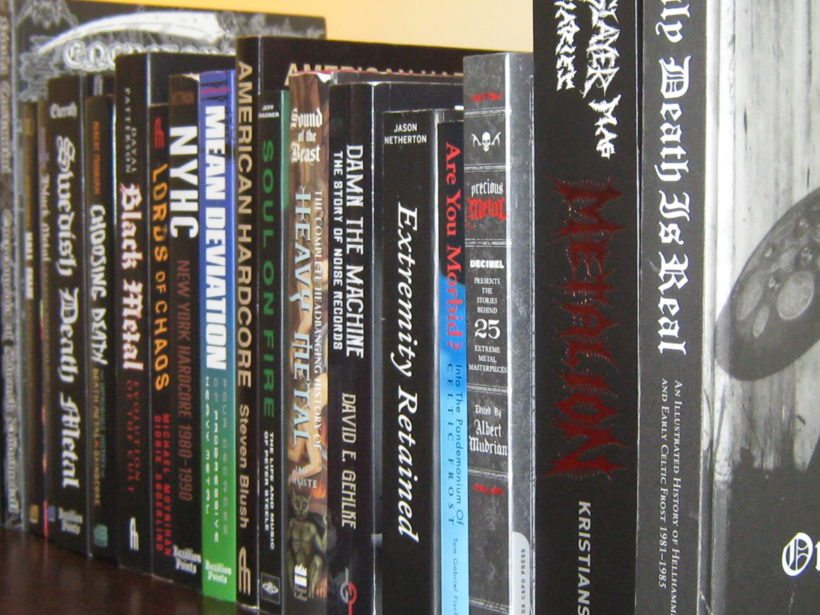

You know Fischer of Hellhammer/Celtic Frost/Triptykon fame. He’s also penned two books, Are You Morbid? and Only Death is Real. What makes his situation as an author unique is that his works were published during two different eras of proliferation and popularity with respect to extreme-music-related reading material. The Celtic Frost-focused Are You Morbid?, originally published in 2000, came during a time when extreme music literature was mostly limited to Lords of Chaos, American Hardcore, Sound of the Beast and Choosing Death. By the time his Hellhammer-focused Only Death is Real was released in 2010, the bookshelf had become far more crowded. Since then, page-turning options pertaining to underground music and culture continue to grow.

“Heavy metal has gone through many incarnations, and people of our generations were already involved in the scene when it was going through these,” says Fischer, in explaining the “why” behind heavy metal literature. “For example, the early ’80s was extremely exciting and revolutionary for our scene, and having lived through that innovative time, there are reminisces about the time and what was missed.”

Adam Parfrey is the owner/operator of Feral House, the original publisher of three of the above-mentioned titles. “Lords of Chaos was the first of these books published [in 1998]. At the time, there was practically no [mainstream] interest in black metal per se, but the true crime background to it fascinated me, so I supported getting a book done on the subject. It sold well enough over the years, but it took awhile to get through the first printing. In regards to American Hardcore [published in 2001], I was a friend of [author] Steven Blush and supported the idea. Albert Mudrian brought Choosing Death to me [in 2004]. I hadn’t yet published a book on death metal or grindcore, and it seemed appropriate to Feral House.”

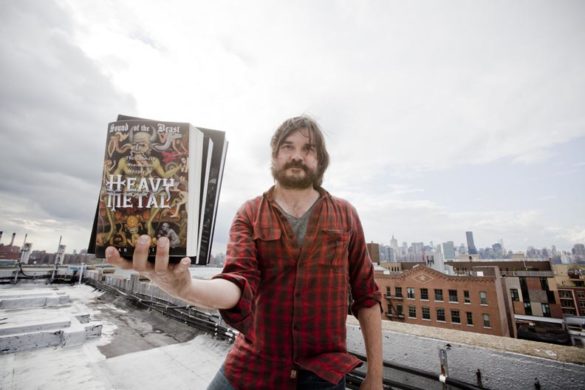

Published a year before Choosing Death, Ian Christe’s Sound of the Beast attempted to fill a void and tell the entire heavy metal story. However, the volume of the subject matter and space limitations forced much of its narrative around the careers of “name” bands like Metallica and Iron Maiden.

“Martin Popoff probably only had four or five books out at the time, but they were mostly discographies and reviews,” says Christe about the lean years of metal books, “and there were books that weren’t music histories at all. I was writing for magazines and ready to move on to writing a book. Metal always burned in my heart, and it was outrageous that in the late ’90s there was nothing about metal, meanwhile there were 17 books about the ’75 – ’77 CBGB’s scene. None of the ’80s writers like Don Kaye, Steffan Chirazi and Borivoj Krgin did it, so I was lucky to be able to walk into a blank slate, which was why I tried to cover everything.”

When asked about the present-day extreme music book scene, Parfrey responds with, “There’s so much of it.” There are countless music-focused autobiographies by, among others, Harley Flanagan, Rex Brown and Dave Mustaine. Additionally, specific topics of coverage have emerged, like Jeff Wagner putting prog-metal under a microscope in Mean Deviation and David Gehlke’s exhaustive study of Noise Records in Damn the Machine. There are album cover compendiums (…And Justice for Art), photo collections (Murder in the Front Row) and who knows how many books about Metallica. Choosing Death has multiple expanded and seven foreign-language versions, and Daniel Ekeroth’s comprehensive Swedish Death Metal tome has been translated into French, Polish and German. Post-Sound of the Beast, Christe founded Bazillion Points for revised versions, future works and for other authors to flesh out other genres, especially those not extensively covered in Sound. The acclaim of the printed word (and pictures!) is definitely growing and, like most phenomena, the reasons are numerous. However, Christe isn’t surprised.

“Up until about 10 years ago, with YouTube, metal history was a written form. There were a couple video magazines and random short interviews on video channels, but basically everything was transferred in fanzines and magazines, by letter or orally. Out of necessity, metalheads were used to reading in a way that other music forms weren’t, and once the credibility hurdle was jumped with Sound, people kept reading.”

And read we have. But why?

I Got Somethin’ to Say. The Times They Are A-Changin’

In considering the growth of metal books, we need to look back to Feb. 13, 1970. That’s the day Black Sabbath released Black Sabbath. We also need to rewind to Nov. 1, 1982, when Venom issued Black Metal. And while we’re at it, let’s skip on over to July 25, 1983, when Kill ’Em All hit the streets. Whether or not you agree with these as loose starting points for the beginnings of specific styles of sound and/or musical movements, one thing that’s undeniable is that none of these albums, bands and what followed in their wake could have been accurately documented without the benefit of time allowing their stories to unfold. It’d be like trying to paint a still-life portrait while your subject matter is still in motion. Books offer the benefit of after-the-fact analysis, and now that metal has a full history and a story to be told, folks like Daniel Ekeroth have taken it upon themselves to tell those tales.

“This is true about everything, not just music or metal,” he says. “It’s impossible to analyze and tell a story about the present. You have no idea what’s going on and where things are going to go. When death metal was going on in the late ’80s, no one thought for a second it was going to be commercial in any way. Most bands had no idea they would ever make an album; it was just about writing a few songs, doing a demo, maybe being mentioned in a fanzine and playing a gig.”

“But, that’s a fantastic development!” enthuses Fischer. “For a very long time, extreme branches of heavy music were ridiculed, even in the metal scene itself, but they meant a lot to a lot of people. That the tide has slowly turned over the years—that it’s now a serious topic for documentation—is fantastic because it’s a history that can vanish very quickly. When you arrive at an older age, you realize that the memories of your youth were also important for other people. It’s great to meet someone from that time and reminisce, and writing a book is almost the same, only that you also get the chance to share with people who weren’t there.”

Graf Orlock and Ghostlimb guitarist/vocalist Justin Smith also runs Vitriol Records and its publishing division, Vitriol Literary, which has bestowed upon the world works by former Decibel managing editor Andrew Bonazelli and some nitwit named Kevin Stewart-Panko. He agrees that “the frequency with which punk, metal and hardcore is being written about today is a function of the temporal conditions between when it existed and now. It’s really hard to put stuff like D.C. hardcore, Dischord Records and Ian MacKaye into a context when there isn’t a trajectory to gauge the change over time. There’s a narrative with different perspectives. For instance, John Joseph wrote Evolution of a Cro-Magnon with his version of things and Harley Flanagan has Hard-Core, which counters some of what Joseph said.”

“It’s also no longer strictly an underground art form. Extreme metal has a popular face,” says Jason Netherton, Misery Index bassist/co-vocalist and author of Extremity Retained, an oral history of death metal’s early days. “It’s still marginal, but there is mainstream representation. I think Albert [Mudrian] said it in an interview years ago that people today know what death and black metal are, even if they don’t listen to it. With that awareness comes a curiosity in underground cultural forms; it’s not only fans buying the stuff and you start seeing it studied in academia. Mainstream culture has caught up with extreme metal in a way. There’s a history with characters, storylines, subjects, iconic releases, and hindsight helps make sense of all the pieces.”

“Time is a big factor,” expresses Dayal Patterson whose The Cult Never Dies and Evolution of the Cult books take in-depth looks at the bands, personalities and events that shaped black metal. “We’re at the point now where we can have more of a historical overview, and in a book, you’re getting the benefit of 20 or 30 years of reflection. You can tell a longer story, give more insight and an understanding about why things are the way they are now with a wider perspective. That’s the strength of a book and the purpose they serve, for both the readers and the writers.”

Driving the popularity of extreme music biographies and histories is the fact that much of extreme music’s early documentation came in the form of fanzines. And as much as we love fanzines—and have published many of them—they had/have limitations. The majority were poorly reproduced, often quite localized, had limited print runs, non-existent distribution and would often disappear after a few issues. “And,” laughs Netherton, who also curates the online zine archive, sendbackmystamps.org, “as an art form they don’t stand the test of time in people’s moldy basements.”

“Most fanzines were horrible, very poorly written, with a lot of inside jokes,” remarks Ekeroth, a former zine-ster himself. “There were language barriers, like South Americans interviewing Swedish bands, and it seemed like every interview was the same 10 questions!”

“Actually,” counters Patterson, “in some ways, fanzines are a bigger influence on the books I do. I’d buy magazines and fanzines when I was young, and you’d find that fanzines weren’t as time specific as magazines, which were there to give the latest news. Fanzines weren’t so tied to a band’s present album cycle and they had unlimited space. Not all fanzines, but some of them.”

Age vs. Youth. Nostalgia vs. Crash Course

If you’re reading this, you’re getting old. We all are. It’s an inevitability that somehow gets overlooked in favor of death and taxes. Everyone ages and no one can stop it, at least until taxes kill you. For those of us continuing to be fans of extreme music, a sense of nostalgia about the glory days has crept onto our radars. There’s a curiosity about what really happened “back in the day” and a well-researched and written book will place events, rumors, anecdotes and musical landmarks into context for folks better able to appreciate and understand their significance. Despite now having jobs, spouses and sprogs, fans are still fans and are thirsting for more knowledge about the music and scene that remains a meaningful part of their lives.

“The generations that lived through the ’80s and ’90s are now in their 40s and 50s and have houses with actual bookshelves in them,” says Netherton. “It’s a way for them to reconnect and hold on to their youth, to experience it again, but also learn more about it.”

“I think Swedish Death Metal came at a perfect time because many people of my generation left the scene, then came back and started to be nostalgic and wanted to remember how things were,” muses Ekeroth. “For my generation, it was like, ‘Oh, yeah, that happened!’ People wanted to look at the pictures, remember things and relive the atmosphere.”

“When I was younger, what prompted to me to buy a book was discovering a topic I was fanatical about and wanted to know everything about,” offers Fischer. “I think that’s very much the same for metal fans today who’ve discovered the existence of a book about something that really, really touches their lives. As metal fans are getting older, they’re discovering connections to roots in unlikely places.”

“It’s what I call the ‘historicization’ of underground music,” says Smith. “People who were involved in this stuff early on are getting older and putting stuff in context. But it’s also why I think there are so many reunion shows and tours these days. There’s way more access to things, and people just getting into music want to see these bands. It’s crazy when a band is playing their first show in 30 years and it’s the biggest show they’ve ever played,” he laughs.

Undoubtedly, new crops of listeners have discovered extreme music via the internet. They may have missed out on having fanzines thrust in their faces at shows, and their listening experience has mostly been via downloading and streaming, but as Ekeroth observes, “A new generation of death metal bands and fans wanted to learn about those times, and because of that, Swedish Death Metal had two audiences.” The internet has rescued a great number of bands from the realms of crippling obscurity, in the process making the exploration of extreme music’s nooks and crannies revelatory and exciting. The index listing off the discographies of untold numbers of Swedish bands in Ekeroth’s book is manna from heaven for metal nerds, as is Patterson revealing that there was/is much more to black metal than Norwegian arson and murder sprees.

“There are people who weren’t there during the formative years,” says Patterson, “and while you don’t want to deny that there are amazing things happening now, it’s pretty hard to argue that the most important years for death and black metal weren’t the ’80s and ’90s. Say you were born in 1990; you’d be 27 now, and even though that isn’t that young, you basically missed out on the ’90s. If you’re into black metal and didn’t start going to gigs until the mid-2000s, there’s huge part of the history you missed, and it’s hard to understand the context just by listening to something in isolation 20 years down the line. That’s where books have their strength, placing this stuff in context and allowing you to guide yourself through the era. It kind of gives you a map to help you curate your journey instead of saying ‘off you go!’ It’s hard enough to appreciate the whole phenomenon and situation even if you were there. If you weren’t there, what hope do you have? Same goes for the artists themselves who didn’t appreciate what they had done until much later. I couldn’t have written my books 10 years earlier because I think some of those people were still too close to those events to speak honestly. They were still in character and still trying to present themselves as something else.”

“The passage of time has made things cool that were once uncool,” remarks Fischer,

with a laugh.

“But you have to be objective about it,” warns Smith. “When I was a kid I had this book with all these old flyers of early punk and hardcore shows: Misfits, Minor Threat, Necros and all these old-school bands. I used to think to myself, ‘Those shows must have been crazy!’ Later on, I’d see pictures of the same shows and there were 30 people there. The explosion of books about the ’80s and ’90s is cool, but you have to watch for things becoming a little artificial.”

Literal Calming Touchstones

Tom Fischer reads the New York Times online every day from his home on the outskirts of Zurich, Switzerland. He enjoys being able to keep up to date with all the news that’s fit to print (yes, we recognize the irony of that statement) via some of the best journalism since journalism was invented. However, he bemoans that reading the online Times—and most other websites, for that matter—is often a tumultuous experience as advertisements split up paragraphs, videos will start randomly playing and lists of recommended stories and more ads flash up and down the screen margins. Granted, advertising is necessary when bills and salaries need to be paid, but so-called “active ads” can be an irritating detraction.

“It’s understandable and the sign of a vastly different time,” comments Fischer, “but a book allows you to have your information in a completely different context and immerse yourself in a topic in a far more superior manner. I know it’s very old-fashioned, but it’s fantastic and that’s its power versus modern media.”

“It’s definitely a generational thing,” explains Smith, who jokes about being on the top end of the millennial generation. “There’s a book by Michael Harris called The End of Absence, which talks about the end of the last generation that grew up without the internet and the generation with total connectivity where you can be on a volcano in Iceland tweeting a picture of shit and there’s wi-fi on airplanes. Unless you consciously turn it off, you’re never unconnected. Turning it all off, sitting down and reading is a break from all that.”

In choosing a physical book, readers are not only allowing themselves escape and engagement, but they’re doing so with subject matter they’re interested in and captivated by. Being able to sit down with a staid or static page allows for focus, control and a settling of the mind. “It’s calming,” proclaims Netherton. “It gives you a chance to step out of the chaos for a moment and step into a different kind of mental atmosphere. It’s an extension of the music people love and gives them something to hold on to.”

“Books are like albums, magical pieces of creation,” says Ekeroth. “I’m a librarian—I work in a school library, which explains why there are so many heavy metal books at my school!—so I’m surrounded by books all the time and I love them. I also think that the internet is getting worse and worse, over the last five years it’s become limited, with people only using Facebook and social media and algorithms guiding you into little corners based on commerce. Books are forever; stuff gets taken down and disappears off the internet all the time.”

“It’s a debrief for your brain,” says Christe. “A book is going to pull you in way deeper than anything else. You’re using all parts of your brain and can get lost in it. There’s no type-and-scroll-type-and-scroll agitation.”

The growth in the popularity of extreme music books parallels the resurgence of vinyl. As sales of black gold continue the annual upward trajectory it’s been on since 2007, booksellers both online and at brick-and-mortar shops have also reported increases throughout the 2010s.

“[Vinyl and books] force you into digesting the information in the way it’s meant to be digested,” states Smith, “and there’s something to actually having it in your hand as well, though I’m sure there are as many people who don’t listen to the records they buy as people who don’t read the books they buy!”

“I think an interest in tangibility is very simple and very true,” opines Christe, who’s witnessed the growing trend toward physical books first-hand through Bazillion Points. “That’s what the rise of vinyl and books are about, and it flows over into an interest in other things that are carefully made and handcrafted, like handmade guitars or craft beer.”

“People are wanting to connect with the music and culture in a digital, post-material world,” reasons Netherton, “and that transcends all generations. It’s not just for the older, nostalgic people. People who have grown up never really owning any of the music are discovering vinyl and books, it’s something that gives them a grasp of the subculture.”

Patterson agrees. “There’s a permanence people are attracted to; they love to send photos of bookshelves with my books on it, and you can see that these things are with them, if not for life, then for a considerable amount of time. It’s an investment of time and space, not a casual thing. I don’t think people casually buy books about extreme metal. They know they’re going to get more from it than reading an interview online or a Wikipedia entry. It’s quality time spent in an era where we tend to rush through content and don’t necessarily appreciate it.”

This feature originally appeared in the August 2017 print edition of Decibel, which is available here. Bazillion Points, Decibel Books and other titles are available here.