News broke earlier this week that MTV News will be moving away from long-form journalism and returning to a more video-based format. It’s particularly alarming as MTV News had only tried the long-form approach for a couple years (in other news, MTV still exists). Additionally, Clrvynt, a music publication dedicated to long-form pieces, seems to have shut down completely, after less than a year in operation. With this news comes the inevitable speculation among music writers about the future of long-form music journalism.

It strikes at the very core of the entire enterprise of music journalism: its greatest strength is its greatest weakness. In his preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde once quipped that “All art is quite useless.” By this he meant that it’s not useful in the way as basic necessities like medicine, food, gas, housing and raw materials. But this is precisely what makes it so important. And where does that leave news reporters, editors, critics and photographers? We’re another layer up from the art itself: we’re producing something most people read for their enjoyment about something they listen to for their enjoyment. The fact that an “industry” – where enough consumers, investors and advertisers paid us to write about something that isn’t a basic human necessity, to the point where it supplied enough for offices, day jobs and benefits – ever existed seems incredible.

Keep in mind, just because day jobs in music journalism are declining doesn’t mean the form itself is in jeopardy. Plenty of us work in other fields and manage to dedicate time to writing detailed, heavily researched articles about The Black Legions or the future of Maryland Deathfest or the intricacies of death metal artwork.

But for writers, earning money makes a difference. Money is the primary means of exchanging goods and services, so it’s pretty damn important. It’s very difficult to sustain a widely read, visually appealing, and consistently updated print or online publication without some kind of monetary incentive. It motivates people to write more, to do more and to invest in gaining more readers. It means having the resources to do more than whip-up a WordPress or Squarespace account and throw the occasional post at your long-suffering, uninterested friends and family on your personal social accounts. If you want people outside of your close circle to support what you’re doing, you need to compete for their time. Competing for that time with something that’s 100 percent a labor of love is very difficult.

This matters for companies as well, and not just in the music world. Yes, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The New Yorker and The Boston Globe are all seeing record-breaking increases in subscriptions in the era of Donald Trump. However, this is partially due to a massive market consolidation, with many local papers going out of business. Additionally, not every publication has a Jeff Bezos that can rescue it with massive capital investments. Profit-based companies can only operate at a loss for so long until they have to do less (remember when Revolver was a monthly publication?), lay people off, or cease operations altogether. It’s sad and brutal, but commerce doesn’t operate on altruism.

Any music publication looking to keep long-form journalism alive and economically viable faces – and has always faced – the following reality: demand for reading material about music must be high enough, and targeted effectively to get cash flowing into the system to pay for the publication to generate the supply at a reasonable price AND then pay its writers in enough wages or stipends to compete for their time. This was hard enough before the digitization of news media and the demand-destroying effects of the 2008 recession. In 2017, the challenge seems even greater.

Why Should We Care About This? Why Is It Important?

In a recent essay in The Baffler, Natasha Vargas-Cooper details the arguments of sociologist Neil Postman, and their relevance to the decline of adulthood in the post-modern age:

Postman makes the case that as society moves away from a print culture—wherein knowledge is amassed in stages, sequentially, forcing greater levels of rigor, maturity, and comprehension on the reader—and toward mass media, we begin to lose the mechanism for civic life. Indeed, Postman contends that greater literacy is inextricably linked with the core defining traits of adult cognition and discourse: “A child evolves toward adulthood by acquiring the sort of intellect we expect of a good reader: a vigorous sense of individuality, the capacity to think logically and sequentially, the capacity to distance oneself from symbols, the capacity to manipulate high orders of abstraction, the capacity to defer gratification.”

The value of music is universal. It cuts across cultures, class divisions, races, genders and age groups, making it a critical part of civic life. By extension, discussion about that music through the written word injects vitality into the culture around the music. To quote Oscar Wilde’s preface again, “Diversity of opinion about a work of art shows that the work is new, complex, and vital. When critics disagree, the artist is in accord with himself.”

I don’t mean to overstate the importance of what we do (“Stand aside evildoers! I’m a music journalist!”), but to identify what makes it worth preserving.

So Is There Hope?

The wider music industry has finally begun growing again since 2015, after a massive 40 percent decline over the previous 15 years. Much of this is driven by the growth in streaming services, though the resurgence of vinyl plays a part as well. On a broad scale, higher economic growth puts money in people’s pockets, which frees them up to spend on pleasurable things. Likewise, the success of record labels, bands, music stores and venues has cascading effects on music journalism.

It reminds me of the scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail where a peasant undertaker walks through a plague-stricken village, hauling a cart of corpses while yelling “bring out yer dead!” He’s approached by another villager claiming to have a corpse to give away. He’s about to accept it until he finds the man isn’t dead! (“I’m not dead!” “I’m getting better!” “I feel happyyyyy!!!”). Perhaps all of us on metal Twitter are the man trying to give away a corpse…but the body is still breathing, with outlets like Decibel, the recently resuscitated Metal Hammer, and Terrorizer are the man inside saying “I think I’ll go for a walk!”

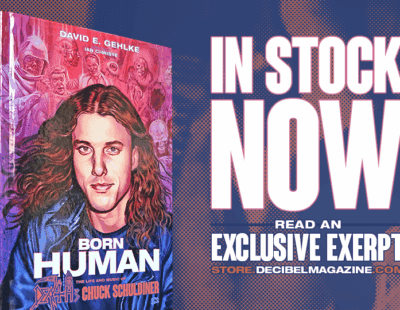

It’s not that long-form music journalism isn’t viable, rather it’s future resides in very specific forms and outlets. Decibel’s model is unique in that the magazine built up enough market share before mass digitization that it gained the required strength to thrive on several fronts: subscriptions (print and digital), retail sales, print advertising, online advertising, concerts and books. Yes, books!

In many ways, the media and various “influencers” oversold the all-consuming nature of the digital age. For the past few years, e-book sales have been declining as print has seen a resurgence in popularity. And as a story in the latest issue of Decibel shows, this trend extends to books about extreme music as well. But what is it about metal that drives its fans to spend money on books about it? In “Only Print is Real,” Kevin Stewart-Panko writes that

“There’s a curiosity about what really happened “back in the day” and a well-researched and written book will place events, rumors, anecdotes and musical landmarks into context for folks better able to understand their significance. Despite now having jobs, spouses and sprogs, fans are still fans and are thirsting for more knowledge about the music and scene that remains a meaningful part of their lives.”

The article contains insightful and optimistic words from the likes of Ian Christe, Thomas Gabriel Fischer, Daniel Ekeroth, Dayal Patterson and others on their ability to get their tomes published. The mere existence of these books should be a hopeful sign, as it means they’re popular enough that people will buy them and publishers will take the risk to spend advance money on authors looking to write more of them. And their power isn’t just in the nostalgia of boomers and gen-Xers who want to dive into their raucous youth, but in younger audiences who want to learn more and get a better idea of the timeline and canon of extreme metal. It’s an excellent, inspiring and worthwhile long-form article.

So while long-form journalism may not be able to prop up an entire industry or sub-industry anymore, there is enough of an audience out there with a need we can serve. And if we do a good job of it, we might be able to grow that audience.

To that end, you can check out the excellent selection of books at the Decibel store!