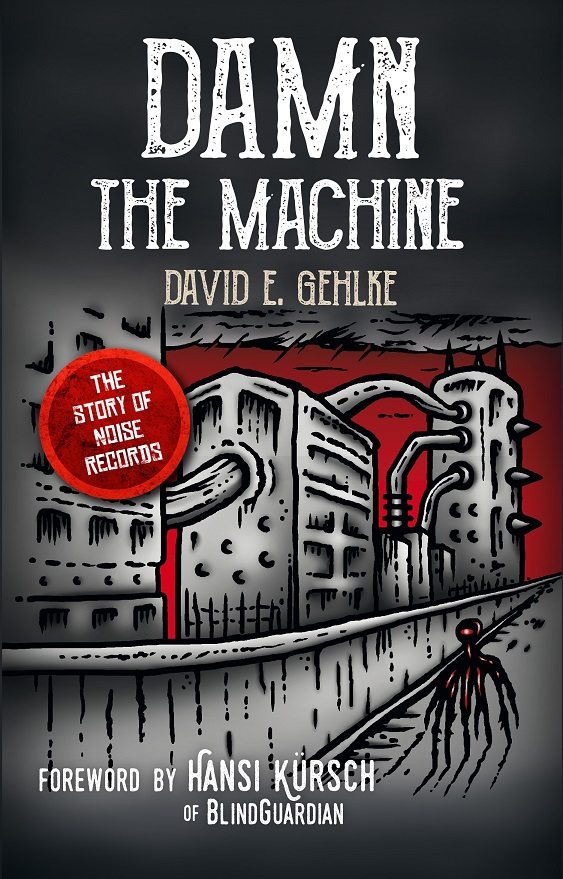

Like you and like me, journalist David Gehlke loves classic Noise Records releases. Unlike you or me, instead of just sitting around fondling our many copies of To Mega Therion, Gehlke has written a book about the label, Damn the Machine: The Story of Noise Records. The book, which is out now on Deliberation Press, details, among other things, how Karl Walterbach started the label out of his anarchist crust-punk roots (seriously) and the turmoil between the label and more or less every band on it.

“People don’t realize that all the stuff that goes on behind the scenes has the largest effect on a band,” says Gehlke, who adds that Walterbach had no creative control over the book and was not included in the editorial process.

We caught up with Gehlke to talk about this project, how Tankard managed to come out in better shape than most Noise bands, what Gehlke’s favourite Noise record is, and more.

Why did you decide to do this book and why Noise?

When you think of band/label relationships and the ones that went wrong, Noise is one of the ones that you think of first, really. This stems to Tom G. Warrior and some of the books he’s put out, where he’s been very difficult on the label, and Helloween’s issues with the label have been very well known, and Kreator, although Mille [Petrozza, vocalist/guitarist] tends to be a little bit more cordial about it… we could go down the list. So that sort of piqued my interest. Karl Walterbach [Noise founder] reappeared on the scene after being away for about 10 years; he’s managing bands now. I sent him an email saying, “Hey, I’m a big fan of the label, I own a lot of your releases, would you be interested in conducting an interview?” We ended up talking for two hours or something like that. I got off the phone and said to my wife, “This guy’s really fun to talk to, he’s got a lot of stories, I may want to approach him about doing a book.” I approached him afterwards and he turned me down; he turned me down two or three times, actually. So it took some cajoling on my end. I always had to have one caveat in there, that we had to interview his bands, that it can not be the Karl Walterbach biography; that would be totally one-sided, and who’d want to read that? He agreed to it, and we got to work on it I think around March of 2014, and here we are today. Noise has such a great backstory, such a great history of bands; you think of all the bands they unearthed and how big they are today, and it just sort of made sense. You have all these great personalities that emerged from the label; it was just this great emergence of all these elements.

Why was he reluctant at first?

Probably because he didn’t know me. I’m an American writer, I’ve never met Karl in person, back when I was approaching him I had just turned 30; I wasn’t around when the label was going on, so I think he may have been a little wary of someone like that taking the book on. Hopefully I was eventually able to show that I knew enough about the label and the bands that we could do something that people would be interested in. It’s not like Karl’s never not wanting for the spotlight; I think over the years he felt a little bit shunned by the scene, because all his bands have been very public about their time with Noise, and Karl’s never really had a platform to respond. So once we got agreement on how we would do the book, he jumped at the chance to share his experiences.

I found it really interesting reading about his early life; he was really political, he ended up in jail, he had this punk rock life that I had no idea he lived. It gave me a really different perspective on the guy.

Back in the ’70s in Berlin, that was a crazy time, for lack of a better term. You had all these college-age kids who weren’t in college but weren’t in high school who didn’t really know what they wanted to do. They flooded the city of Berlin, they squatted, they found empty buildings and just lived there. The city didn’t boot them out, and Karl was part of that community. They were very anti-authority, anti-everything. Karl got into punk just as a function of living there. Had he not been living there, he may not have gotten heavily involved in the punk scene and saw, hey, there’s a market for this, maybe I’ll start my own label; he started Aggressive Rock Produktionen, his first label, ran that for a few years, then realized punk sort of hit the wall after a certain amount of time; not to discount punk, punk is great, obviously, but come ’82, ’83, metal was about to explode and he saw that there was this wide-open landscape, untapped territory in mainland Europe, and no one’s doing anything.

It was also really interesting reading about his relationships with his bands. It says in there that he’s never really been close to any band on his label on a personal level; that’s really difficult for some guys, like Tom Warrior.

Yeah, you’re quite correct. Karl wasn’t friends with any of his bands, how about we say that? Karl saw it at a business level, and that alienated him from a lot of his bands, especially Tom Warrior. Tom and Martin [Ain, Celtic Frost/Hellhammer bassist] made it very clear that when Karl discovered Hellhammer, they saw him as a father figure, almost; here’s this guy that really wasn’t all that much older than they were, but both of them with their backgrounds being what they were, they didn’t really have that male authority figure in their life, or someone they could look up to, and they really hoped it would have been Karl, but Karl just wasn’t having any of it. Karl was more interested in putting albums out and seeing how they would do and signing new bands. He wasn’t there, really, to nurture his bands, and that really rubbed Tom especially the wrong way. He was so disappointed when Karl started giving him a hard time, probably around To Mega Therion, about things, that’s really when it started to nosedive. Karl was a business-first guy, which is interesting because he has no business background; his degree is in engineering. So it’s not like he went to business school or set out to be a bean counter. He loved signing bands, but Karl was not invited to any birthday parties or anniversaries or weddings during his time running Noise (laughs).

There’s one point in the book where Karl calls Chris [Boltendahl] from Grave Digger an “idiot” and Tom says “he screwed all of us over.” The tension between band and label is clear all throughout this book.

One thing with Karl is he really stuck to his guns on a lot of things. Usually there’s some type of give and take between band and label, but on some things, like Celtic Frost when they were making Into the Pandemonium, Karl just did not understand that album, and he was bugging Tom and Martin all the time about it, and he was really worried that because it was such a directional change it would alienate their fanbase, when the opposite happened: it’s their most brilliant album. Karl, there was always some type of tension between he and his upper-tier bands. He and and Peavy Wagner from Rage, they never hit it off, there was always some issues there, Peavy never trusted Karl, probably because Karl saw them as being a mid-tier band. Chris from Grave Digger… Grave Digger may have been the first band to sign to Noise, but once Helloween or Running Wild passed them on the sales figures, Grave Digger was sort of second fiddle, then they made the dreaded directional-change album with Stronger than Ever when they were Digger, and they were done in Karl’s eyes. Those two, they will not be partying down any time soon (laughs).

There are so few labels where, especially back in the ’80s, where if you talk to the bands, the bands would say they were great. Across the board bands more or less hate their labels. Why do you think that is? Is it because bands don’t realize what they’re getting themselves into or is it because all labels are crooks?

That’s a really good point and that’s sort of why I did the book, actually. The recurring line I heard throughout the book from people associated with the label or various managers was, “The first thing the band does is blame the label. Something goes wrong, what do they do? They blame the label.” And that’s tough for some label people to swallow because they’re investing their money and time and energy into a band and if an album doesn’t go well or doesn’t have proper sales figures or doesn’t meet expectations, the band’s automatically going to point their finger at the label, not realizing that, well, maybe they didn’t make good enough of an album. Especially in the ’80s, there never really was great relationships between bands and their labels. But with Noise it seemed so much more personal and heated, it seemed like it was so much more difficult than the other ones.

Why do you think that was?

I think a lot of it had to do with Karl, obviously, and the wages some of these bands were making. The old saying is “If you can make it through your first record deal, you’ve made it.” Karl always said he wasn’t responsible for any of his bands’ financial well-being, and that was reflected in the deals he gave his bands. A lot of these guys could barely make a living being a Noise band. Sure enough, when bands started to have success, they wanted to see more money and think they should be compensated accordingly, and who could disagree with them? You can’t. Celtic Frost were dirt poor during their highest peak, which was Into the Pandemonium. Helloween was the first Noise band to reach seven figures, and they had no money either. So, of course, you work your butt off and you have success and you have thousands of adoring fans, and you’re not seeing anything for it? Absolutely, you’re going to be bitter about it. And these were pretty standard deals for the time, not just limited to Noise Records.

It’s interesting that Tankard were the one band who were doing okay financially because they were a part-time band.

That was something I kept on harboring on throughout their chapter; they made a decision pretty early on that they weren’t going to live solely off the band. It paid off for them; they’re still around today, and they’re certainly bigger now than they were on Noise. They had a few issues with Karl here and there, but the animosity certainly isn’t there between Tankard and Noise, and a lot of it has to with the fact that they were a part-time band. They were pretty realistic about their career; they understood that they had their own gimmick being a beer metal band (laughs). How serious were people going to take them? Well, people took them seriously, they’re great musicians, but when 90 percent of your songs are about beer and alcohol and its consequences, how serious are people going to take you compared to a band that’s serious all the way through, like Celtic Frost or Kreator? But Tankard was able to make out pretty well for themselves while on Noise.

So what was your big takeaway from writing this book and what did you learn?

Outside of the generic response that there are two sides to every story, a lot of it stems from dealing with Karl and seeing his side of things. Deep down, Karl wanted what was best for his bands, but it spiralled out of control. It’s that snowball/runaway train scenario; I think that’s what Noise Records really was. The label just blew up so fast between ’84 and ’87 and ’88, those were the peak years. After that, Cold Lake comes out, Helloween leaves the label, Kreator tops out after Coma of Souls, does Renewal, which doesn’t do as well, and all these other bands start leaving the label. I think Karl would tell you that he wishes he could go back and maybe slow things down a little bit, give things a little more space to breathe and maybe ease up on a few things here and there. That was my biggest takeaway: I don’t think Karl ever anticipated the label becoming as big as it did. Once it did, it just got out of control, and he, ultimately, paid the price for it in the ’90s. Another thing is that sometimes it’s not a bad thing to go against your gut; Karl hated death metal, and it went against his gut to think about signing those bands. If Karl eased up a little bit and would have signed some death metal bands, Noise’s fortunes may have changed in the ’90s. It’s certainly possible.

You mention this in the book, but I’ll ask again: what do you think is the best Noise album ever?

Helloween’s Keeper of the Seven Keys Part II. I know a lot of people would disagree with me (laughs), and there’s some stiff competition. All the Celtic Frost albums until Cold Lake, even though I know there are some people who find value with that album among the Decibel staff. I don’t disagree with them; there are some good riffs on the album. I don’t dismiss Cold Lake at all. But I’d say the second Keeper album is the ultimate Noise album, and probably the ultimate power metal album. When you think that everything Helloween did on that album has been copied down the line by so many power metal bands, song structures, melodies, drumming, how to present yourself in an epic way without being overly cheesy… Helloween mastered that, even though they were goofy and they were light-hearted. No other metal band was like that, back then, four guys smiling… Anthrax was doing something similar, but Helloween was far more goofy and jovial.