The Book of Opeth is, essentially, a glorified biography, with slightly more detail than what used to be up on the band’s website, www.opeth.com (now defunct?). There are the requisite quotes from most of Opeth’s band members. Though it would’ve been nice to have ex-drummer Anders Nordin or founding member David Isberg’s perspective or old friend/producer Dan Swanö quoted, frontman and Opeth brainchild Mikael Åkerfeldt makes up for it, telling alluring tales of musically-inclined, sonically adventurous but industry-inept Swedish kids with a dream. The Book of Opeth really paints a quaint, but informative picture of a band that started with nothing—other than groundbreaking take on death metal—and ended up, through hard work, personal and professional alignment, and a bit of luck, at the very top of the extreme metal heap.

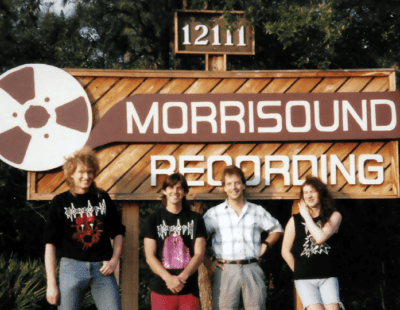

The Book of Opeth is divided into logical chapters. The early years—up through Still Life, actually—are the most interesting. There’s a lot of personal information, shared by Åkerfeldt and ex-sideman Peter Lindgren, with supporting photos, some of which haven’t been seen in full, like the infamous top hat session; turns out there’s rolls of Opeth in various top hat configurations, all of which are funny in retrospect. Really, it’s about the photos though. Up to Still Life, Opeth’s bandshots were barely planned, and almost always in reference to a band photo on an obscure ‘70s sleeve, though I’m not too sure the Sörskogen shadow session refers to any specific album. Again, though, much of the story, as detailed by Åkerfeldt, is familiar stuff. None of which is in a single location, such as in this book, but there’s a lot of history—interviews and fanpages—that’s out there if looking at old Angelfire and Geocities sites on the Wayback Machine is considered a single location now. Still, stories of the My Arms, Your Hearse recordings and Nordin’s departure are nice to have in print, both of which nearly tore Opeth into oblivion. Or, was that the Deliverance and Damnation sessions?

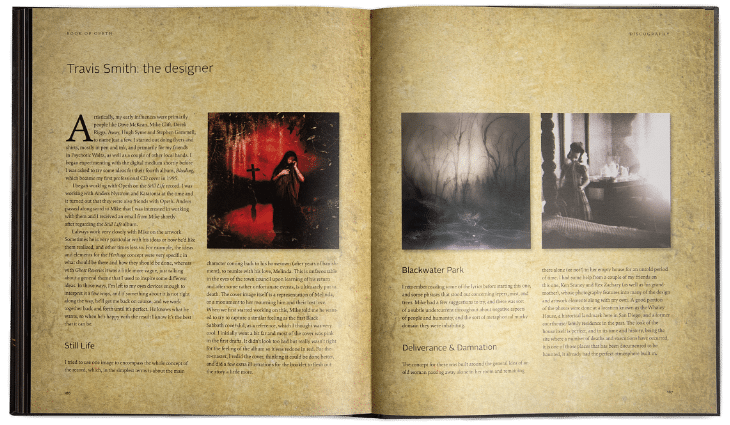

The later years, particularly starting with Blackwater Park, are slightly less intriguing. Even though Opeth didn’t know what they were doing when they weren’t writing songs, the ascendant part of the Swedes’ career shows more temerity, and the fact that they had an engine—manager Andy Farrow—behind them. I remember when Åkerfeldt, over pizza at an Upper Darby, Pennsylvania restaurant, asked me to manage Opeth. As a friend and a fan, I had to say no, as I was just as clueless as Åkerfeldt. After Blackwater Park, Opeth’s rise to the top was planned and logical. Signing to Roadrunner Records was likely the smartest move in the band’s history; though being forced to sign to Music For Nations was only positive insofar as the group’s respective history is concerned. They worked hard under Roadrunner, producing avant-death classics in Ghost Reveries and Watershed.

As The Book of Opeth comes to an end, one thing is evident, even if Opeth don’t say it themselves: they’re true artists. Musicians in an era of non-musicians and pretenders, where marketing and visuals and social media bullshit are more important to woodshedding and understanding that music, in its purest form, comes from the other, not from a computer rigged to hide limited skillsets. Opeth are musicians, formerly and yet still firmly rooted in death metal. The Swedes are in it for the long haul. Careers, not stints, as musicians. That doesn’t mean The Book of Opeth isn’t without its issues. There’s a certain lack of cohesiveness to the narrative. Because it’s told chiefly by Opeth, perspectives—fans, publicists, etc.—are lost. Without them, The Book of Opeth feels, at times, a bit cold and, in some cases, lacking context.

Certainly, I can’t comment on the physical qualities of the book. Quality of printwork? Uncertain. Looks professional. Quality of binding. Looks like it’ll last from the unveiling video. Layout work, pretty ‘zine-like with its inverted text and photo layout, which adds to the overall aesthetic that Opeth were, first and foremost, an organic, music-first band. That also means no 7”, as the digital version isn’t the Classic or Signature Edition either.

In the end, The Book of Opeth is for fans by Opeth. The fair weathers need not apply or order or appreciate. So, it’ll sit nicely next to Lukasz Dunaj’s Behemoth: Devil’s Conquistadors, any of Bazillion Points’ superb tomes to metal, and Albert Mudrian’s (cheap plug) revised Choosing Death on discerning shelves everywhere.

** The Book of Opeth can be ordered HERE.