Maybe someday Decibel will dedicate an entire issue to a band like Blood Incantation, a powerful entity with a relatively brief history that can be entirely encapsulated in 60-odd pages. Maybe then a one-band-focused issue will be capable of exploring all that it has meant to be part of that band. One thing’s certain – no tale as rich and winding as that of Neurosis could be told in anything less than a quadrilogy. We tried, back in the now-sold-out issue #144, to tell you as much of the story as we could, but there’s a difference between laboring over a journalistic Tower of Babel and telekinetically conjuring a clockwork leviathan out of the Martian sand… We knew before we began that the goal was simply to shed light on a small corner of the Neurosis experience.

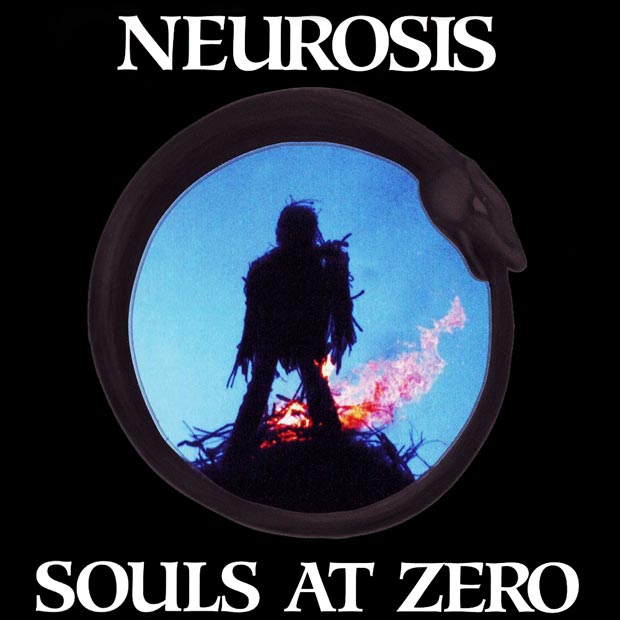

The obvious truth is that no collection of printed words can give clear, full shape to the thirty years of writing, recording, touring, hanging out, leaning on each other and raw living that have defined Neurosis. In our Hall of Fame piece on 1992’s Souls at Zero, though, we had the unique opportunity to speak with former members Simon McIlroy (keyboards, samples, etc.) and Adam Kendall (film loops, color wheels, other visual elements), two super friendly guys with a lot to contribute. Today, we offer the outtakes from our conversation with Mr. McIlroy (watch this space for a full interview with Adam Kendall in the near future), in an attempt to add one more tier to Decibel’s monument to one of the most belligerent, purest and highly regarded bands of the genre. Continue reading for a glimpse into the chaotic influence-blender behind the multidimensional approach to sound and music, as well as the story behind that burning wicker man on the cover of Souls.

What were you doing before joining Neurosis?

I had been in a local band as a bass player. It was a completely different style of music. It was more of a kind of a pseudo-Sisters of Mercy kind of gothy thing. That was just an opportunity that came along and I got involved in that. Simultaneous to that I’d been doing experimental music on my own for a long time. I had a sampler and a four-track, a multi-track cassette player and I used to do a lot of experimental music with Adam Kendall, who joined Neurosis at the same time as me to run the visuals. Adam and I co-designed the visuals for Neurosis and then he ended up running it. Adam and I have been friends since we were teenagers. We were doing a lot of experimental music, which is more the stuff that led me directly into being involved in Neurosis. I was still in the other band and things got a little tense because Neurosis took up more and more of my time and I eventually had to quit the other band, kind of on bad terms, but I don’t think they ever played anything more than local gigs, and I went with where the action was.

What was your artistic connection to what Neurosis were doing?

It was very much part of that modern, primitive industrial era, and when I say industrial I don’t mean Front 242. This was more like Throbbing Gristle. We were influenced by everything from tape cut-ups to Nurse with Wound. We really enjoyed doing experimental sound stuff, and a lot of it was absolute garbage, as most of that music is… a lot of those bands put out really great albums and occasionally they’ll put out some really shit albums, too. It’s just what you’re going to get when you get into experimental music. Some guy screaming into a microphone through some weird effect for twenty minutes isn’t necessarily great, and other times you’ll end up with something like Current 93’s Dogs Blood Rising and Nature Unveiled, which are brilliant, timeless industrial experimental records.

We had a mutual friend with the band, this guy named Randy. He was this kind of anarchist experimental performance artist. He was really into tape trading and bands like Amebix and Skinny Puppy, any kind of obscure, dark noise. We were friends with him through our social scene. He used to do weird performance art things up in the quarries up in the hills behind where we lived, or he’d invite people with invitations written on skin fragments or something, and he’d do shadow plays with Einstürzende Neubauten blasting, and then set off fireworks. Really weird psychedelic stuff. Randy was this weird kind of chaos magician, a mutual friend with Neurosis. He was a big Neurosis fan. Randy referred me to them. We agreed to get together and jam, and I brought my sampler and we jammed and screwed around a little bit, and we decided to give it a try.

What precedent did you have to help you develop ideas for the work you did in Neurosis?

There were other bands that used samples at the time. I believe White Zombie was [happening] around then, but that was a totally different sound than anything they were going for, but there were other bands that started using samplers with their music. Grotus had a keyboard player, and we toured with them.

In the early 90s, the underground rave house music scene started to take a foothold. Adam and I were influenced to check that stuff out by Psychic TV, which had gotten into the whole acid house thing at the time. For Psychic TV, it was all about pushing the massive amounts of mind-altering drugs and crazy electronica. One of the big things at raves in the Bay Area were these psychedelic visuals, and this was a direct lineage from the psychedelic artists in the Bay Area in the sixties. All the bands that played at the Fillmore, all the psychedelic bands in the Bay Area used to have light shows. Little did we know these were a lot of the same guys who had done the psychedelic visuals for the bands back in the sixties, doing it now at these raves. They were all old dudes who were all crusty and tweaked out, but they came across this new scene that had a use for their talents.

We saw this stuff and got inspired. I think the closest thing to a mutual interest for the visuals that Adam and I brought was maybe Skinny Puppy. They did a lot of psychedelic projections and films in the background while they were performing. We had a little bit of know-how from seeing how this stuff was done. We started putting together a light show that we could do at some of these raves, because we knew some of the promoters. Simultaneously we were designing the Neurosis light show. Obviously the visuals we were doing for raves were more psychedelic, mindscape stuff. The stuff we were doing with Neurosis was crucified bodies, mountains of bodies being bulldozed, war fields. It was a very different aesthetic, but we used the same techniques.

Did you personally know other people who were working in similar ways at that time?

I talked to other keyboardists that we ran into at the time, and because of how much we toured and where we went around the world, I ended up with friends in random different bands, from Grotus and EMF. I talked to them and I realized I had made my job way harder on myself, because most of those bands played with a prerecorded track. They had their keyboard parts mostly recorded, and then they’d play lead parts along with it. Maybe I didn’t know any better or maybe I liked the challenge, but whenever we played live, all the keyboard parts were being played off of a sequencer. Probably I was inspired by bands like Skinny Puppy and Kraftwerk that I knew performed that way. And the keyboard parts were so layered and so multi-instrumental, there was no way I could play everything even if I wanted to. I had two keyboards – an upper keyboard and a lower keyboard – and I would play as many parts as I could but because the parts were so complicated and multi-layered, some parts had to be sequenced. Sound collage or soundscape parts had to be sequenced.

So in order to perform the stuff, we had to play along to a click track, which Jason listened to through earphones. It would start with four beats on the click track and then the sequences would start, drums would come in. We were all very well rehearsed and the songs were written out like clockwork. But it was the only way to have a break in the song where there’s a multi-instrumental orchestral thing with cellos, violins and flutes. That’s how we had written the songs, and we were determined to be able to reproduce them live.

I think we were definitely overly ambitions, and there was definitely a certain amount of overkill in the way we were performing and what we were performing, because to be quite honest, our sound was so dense on the records, I don’t even think you can hear the keyboards half the time. Live, what you heard really depended on where you were in the audience. We all played through full stack amps, including my keyboards, so depending on whether you were on the left side of the stage, the right side or the middle, you’d hear different stuff. Obviously there were monitors, but a keyboard or sampler playing through a full-stack amp next to another full stack playing guitar and another with bass, there was just too much going on. We didn’t really know what we were doing when we started. We were just making it up. Dave’s bass sound was so huge as it was, I don’t know that it needed chords played by cellos through distortion through a full stack, but we did that anyway because we didn’t know any better.

There was no master plan, it was an opportunity that came up, it sounded like fun, I enjoyed it for the few years I was in there – I enjoyed the touring, I enjoyed the records – and it had its ups and downs. There are challenges anytime you’re doing something that ambitious. At one point we were trying to figure out the mix, and Jello [Biafra, Alternative Tentacles] had come down and we did a mix down onto a cassette tape and he went out to listen to how it sounded in his car, because he said that’s the lowest common denominator for how people are going to hear this music, so it if it doesn’t play that way then it doesn’t matter how it sounds in the studio.

Did you have any particular goals or philosophies with the sounds you used?

This was in an era before clearances were a big deal, and we also weren’t exactly White Zombie or being played on MTV, so I think we got away with sampling a lot of stuff that, in this day and age, a band wouldn’t necessarily get away with. We definitely sampled some edgy stuff and some cultural touchstone sounds. I don’t know if people knew what they were hearing, because it was so processed and so rendered, after effects you may not recognize it easily, it may almost be a subconscious ring.

If I had an overriding philosophy or emotion or approach, it was to make it as intense, as loud, as visceral… There was a component to our live shows that you would never really have gotten on the records. Typically at the end of every show, it would end up turning into this feedback deconstruction of sound, with the band detuning their guitars and breaking strings, and I would start going into tape collages, tape loops, and start ramping up reverb cycles and echo cycles, and it would turn into this crazy sound collage meltdown. The visuals would go into crazy overdrive. It would basically end on this nightmarish meltdown crescendo. That was a component of our live shows that I don’t think was ever captured on record. But it was definitely part of the experience of seeing Neurosis at that time.

I know that one of the influences for bringing in the flutes and the violin and tribal drums, they were hearing bands like Current 93, albums like Earth Covers Earth, and started getting into this dark, neo-folk thing. There was a band called Comus, they were this dark pagan neo-folk band that heavily influenced the Current 93 of that era, and early Death in June, when they were collaborating with Boyd Rice. Some of those early Death in June sound collages were similar to what we were doing at the end of our shows, like the Wall of Sacrifice album, but with feedback from guitars and crazy drum breakdowns.

When did you start hearing people saying that Souls was a special album?

I don’t know that it was ever about which record was so influential. It wasn’t that long after I quit the band that I would run into people. I remember being down in Long Beach, probably in the mid-90s, I was actually at the Skunk Records office with the band Sublime, and one of their guys was a huge Neurosis fan. Sublime’s the farthest thing from Neurosis, but one of their roadies was a massive Neurosis fan. The fans that were into Neurosis at the time, it was one of those things, like they would go from show to show, to see as many shows on the tour as they can. They were hardcore fans. It wasn’t like the casual fan. So I always knew there were people who were way, way into it.

Getting distance from the band, graduating college, starting my career, you get separated from it, so you do run across somebody once in a while. Nineteen out of twenty people had never heard of the band, so you usually get that glassy-eyed expression, and then occasionally someone is like, “Oh my god, you were in Neurosis!” It’s always kind of a cool thing to hear.

Right now, I’m driving to Riverside to take my wife to get a tattoo – I might get some work, too – and the artist we’re going to I met through mutual interests we had. I was with Adam Kendall, and I was getting tattooed by him, and somehow Neurosis came up and he found out that we were in Neurosis and he said, “Those are two of my favorite albums ever.” It’s not so much an ego-stroking feeling, but from more of an altruistic sense, knowing that you were part of something that means so much to people is a cool feeling. There’s also an ego component to it, I can’t say that there’s not but…

Are there songs that you still feel connected to?

When I quit the band, I quit completely. I decided I was done, and they probably had decided they were done with me as well. The last tour we went on was brutal and there were a lot of challenges on that tour. So when I left, I was just done. I didn’t want to hold on to anything. I met with the band one time after I quit and downloaded all my samples to Noah because he was taking over for me and I gave him all my samples, copies of all my tapes. After that, I pretty much walked away from it. I don’t think I’ve ever listened to those albums completely since then. Although if you played it back for me and I sat and listened to it, it would probably bring back all kinds of memories. [Looking back,] it was never with disdain or regret, it’s just when it’s time for the next phase of your life, you just move on and don’t look back. I’m so proud of the work I did at the time. I gave 150% of myself, whether on record or on tour.

You helped put together the photo shoot for the album’s cover?

For the cover of Souls at Zero, we wanted to use a shot of the Wicker Man from the movie The Wicker Man. We had comped it up, we knew the shot we wanted to use. We went to try to license it, and they gave us some crazy number. There was no way in hell we were gonna pay it. I don’t know what the number was, but it was an ungodly number that we couldn’t afford and weren’t gonna be able to come up with. So we decided to build our own wicker man. That wicker man burning on the cover of that album, we built ourselves in the back of Steve’s parents’ house. A bunch of us all got together on a weekend and built that thing. We drove it out to the beach, hauled it up on top of a rock. We had a professional photographer there. We set it on fire, and it hadn’t occurred to anybody to build an infrastructure in this thing. We literally just built the thing out of twigs, so by lighting it at the bottom first, what’s the first thing that happened? The legs burned through and it toppled over. Miraculously the picture that ended up on the cover was a picture I took, and it was one of the only shots of it burning but in tact. It wasn’t even intended that I would take the picture, but we got lucky. The sunwheel made out of trees was a project I had done in an art class, a screenprinting class.

Final thoughts?

The band tended to be a very dark band, as far as the look and the presentation. To some extent, there was a little bit of creative tension with the approach I took, and I think that helped the music we created. I think the sound on that record comes from this weird harmony that came about. The background they had, the sound they came from had nothing to do with the stuff I was influenced by at the time. But I think that collision and blending of influences is one of the things that created the sound on that record and maybe is one of the things that makes the record stand out as memorable.

Listen to the Neurosis discography at their Bandcamp site.